Dunstanburgh Castle

| Dunstanburgh Castle | |

|---|---|

| Northumberland | |

Dunstanburgh Castle from the south-east | |

| Coordinates | 55°29′28″N 1°35′36″W / 55.4911°N 1.5932°W grid reference NU258220 |

| Type | Edwardian castle |

| Site information | |

| Owner | English Heritage, National Trust |

| Open to the public | Yes |

| Condition | Ruins |

| Site history | |

| Materials | Sandstone, basalt, limestone |

| Events | Despenser War Wars of Scottish Independence Wars of the Roses Second World War |

Dunstanburgh Castle is a 14th-century fortification on the coast of Northumberland in northern England, between the villages of Craster and Embleton. The castle was built by Thomas, 2nd Earl of Lancaster between 1313 and 1322, taking advantage of the site's natural defences and the existing earthworks of an Iron Age fort. Thomas was a leader of a baronial faction opposed to King Edward II, and probably intended Dunstanburgh to act as a secure refuge, should the political situation in southern England deteriorate. The castle also served as a statement of the Earl's wealth and influence and would have invited comparisons with the neighbouring royal castle of Bamburgh. Thomas probably only visited his new castle once, before being captured at the Battle of Boroughbridge as he attempted to flee royal forces for the safety of Dunstanburgh. Thomas was executed, and the castle became the property of the Crown before passing into the Duchy of Lancaster.

Dunstanburgh's defences were expanded in the 1380s by John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster, in the light of the threat from Scotland and the peasant uprisings of 1381. The castle was maintained in the 15th century by the Crown, and formed a strategic northern stronghold in the region during the Wars of the Roses, changing hands between the rival Lancastrian and Yorkist factions several times. The fortress never recovered from the sieges of these campaigns, and by the 16th century the Warden of the Scottish Marches described it as having fallen into "wonderfull great decaye".[1] As the Scottish border became more stable, the military utility of the castle steadily diminished, and King James I finally sold the property off into private ownership in 1604. The Grey family owned it for several centuries; increasingly ruinous, it became a popular subject for artists, including Thomas Girtin and J. M. W. Turner, and formed the basis for a poem by Matthew Lewis in 1808.

The castle's ownership changed during the 19th and 20th centuries; by the 1920s its owner Sir Arthur Sutherland could no longer afford to maintain Dunstanburgh, and he placed it under the guardianship of the state in 1930. When the Second World War broke out in 1939, measures were taken to defend the Northumberland coastline from a potential German invasion. The castle was used as an observation post and the site was refortified with trenches, barbed wire, pill boxes and a minefield. In the 21st century, the castle is owned by the National Trust and run by English Heritage. The ruins are protected under UK law as a Grade I listed building and are part of a Site of Special Scientific Interest, forming an important natural environment for birds and amphibians.

Dunstanburgh Castle was built in the centre of a designed medieval landscape, surrounded by three artificial lakes called meres covering a total of 4.25 hectares (10.5 acres). The curtain walls enclose 9.96 acres (4.03 ha), making it the largest castle in Northumberland. The most prominent part of the castle is the Great Gatehouse, a massive three-storey fortification, considered by historians Alastair Oswald and Jeremy Ashbee to be "one of the most imposing structures in any English castle".[2] Rectangular towers protect the walls, including the Lilburn Tower, which looks out towards Bamburgh Castle, and the Egyncleugh Tower, positioned above Queen Margaret's Cove. Three internal complexes of buildings, now ruined, supported the earl's household, the castle constable's household, and the running of the surrounding estates. A harbour was built to the southeast of the castle, of which only a stone quay survives.

History

[edit]Prehistory – 13th century

[edit]The site of Dunstanburgh Castle in north-east Northumberland was probably first occupied in prehistoric times.[3] A promontory fort with earthwork defences was built on the same location at the end of the Iron Age, possibly being occupied from the 3rd century BC into the Roman period.[3] By the 14th century, the defences had been long abandoned, and the land was being used for arable crops.[4] Dunstanburgh formed part of the barony of Embleton, a village that lies inland to the west, traditionally owned by the earls of Lancaster.[5]

The origins and the earliest appearance of the name "Dunstanburgh" are uncertain.[4] Versions of the name, "Dunstanesburghe" and "Donstanburgh" were in use by the time of the castle's construction, however, and Dunstanburgh may stem from a combination of the name of the local village of Dunstan, and the Old English word "burh", meaning fortress.[6]

Early 14th century

[edit]Construction

[edit]Dunstanburgh Castle was constructed by Thomas, 2nd Earl of Lancaster, between 1313 and 1322.[7] Thomas was an immensely powerful English baron, the second richest man in England after the King, with major land holdings across the kingdom.[5] He had a turbulent relationship with his cousin, King Edward II, and had been a ringleader in the capture and killing of Edward's royal favourite, Piers Gaveston, in 1312.[8]

It is uncertain exactly why Thomas decided to build Dunstanburgh.[9] Although it was located on a strong defensive site, it was some distance from the local settlements and other strategic sites of value.[9] Thomas held some lands in Northumberland, but they were insignificant in comparison to his other estates in the Midlands and Yorkshire, and until 1313 he had paid them little attention.[10]

In the years following Gaveston's death, however, civil conflict in England rarely seemed far away, and it is currently believed that Thomas probably intended to create a secure retreat, a safe distance away from Edward's forces in the south.[11] He also probably hoped to erect a prominent status symbol, illustrating his wealth and authority, and challenging that of the King.[12] He may perhaps also have hoped to create a planned town alongside the castle, possibly intending to relocate the population of Embleton there.[13]

Building work on the castle had commenced by May 1313, with labourers beginning to excavate the moat and starting to construct the castle buildings.[14] Some of the outer walls may have been built by workers from Embleton as part of their feudal dues to Thomas.[15] The operations were overseen by a mason, Master Elias, possibly Elias de Burton, who had been previously involved in the construction of Conwy Castle in North Wales.[16] Iron, Newcastle coal and Scandinavian wood was brought in for use in the project.[17] By the end of the year £184 had been spent, and work continued for several years.[16][nb 1] A licence to crenellate – a form of royal authorisation for a new castle – was issued by Edward II in 1316, and a castle constable was appointed in 1319, charged with defending both the castle and the surrounding manors of Embleton and Stamford.[19] By 1322 the castle was probably complete.[16]

The resulting castle was huge, protected on one side by the sea cliffs, with a stone curtain wall, a massive gatehouse, and six towers around the outside. A harbour was built on the south side of the fortress, enabling access from the sea. Northumbria was a lawless region in this period, suffering from the activities of thieves and schavaldours, a type of border brigand, many of whom were members of Edward II's household, and the harbour may have represented a safer way to reach the castle than land routes.[20]

Loss

[edit]Thomas of Lancaster made little use of his new castle; the only time he might have visited it was in 1319 when he was on his way north to join Edward's military campaign against Scotland.[17] Civil war then broke out in 1321 between Edward and his enemies among the barons. After the initial royalist successes, Thomas fled the south of England for Dunstanburgh in 1322, but was intercepted en route by Sir Andrew Harclay, resulting in the Battle of Boroughbridge, in which Thomas was captured; he was later executed.[21]

The castle passed into royal control, and Edward considered it a useful fortress for protection against the threat from Scotland.[21] Initially it was managed by Robert de Emeldon, a merchant from Newcastle, and protected by a garrison of 40 men at arms and 40 light horsemen.[22] Roger Maduit, a politically rehabilitated former member of Thomas's army, was appointed as constable, followed by Sir John de Lilburn, a Northumberland schavaldour in 1323, who was in turn replaced by Roger Heron.[23]

Maduit and the castle's garrison took part in the Battle of Old Byland in North Yorkshire in 1322, and the garrison was subsequently increased to 130 men, predominantly light horsemen, and formed a key part of the northern defences against the Scots.[24] By 1326, the castle was given back to Thomas's brother, Henry, 3rd Earl of Lancaster, with Lilburn returning as its constable, and continued to be of use in defence against the Scottish invasions over the next few decades.[25]

Late 14th century

[edit]

Dunstanburgh Castle was acquired by John of Gaunt, 1st Duke of Lancaster through his marriage to Henry of Lancaster's granddaughter, Blanche, in 1362.[26] Gaunt was the 3rd son of King Edward III and, as the Duke of Lancaster, was one of the wealthiest men of his generation. He became the Lieutenant of the Scottish Marches and visited his castle in 1380.[26]

Dunstanburgh Castle was not a primary strategic target for Scottish attack, as it was positioned away from the main routes through the region, but it was kept well garrisoned during the Scottish wars.[27] The surrounding manor of Embleton had nonetheless suffered from Scottish raids and Gaunt had concerns over the condition of the castle's defences, ordering the building of additional fortifications around the gatehouse.[28] Part of the surrounding lands around the castle may have been brought into agricultural production at this time, either to feed a growing garrison or to protect the crops against Scottish attacks.[29]

In 1381 the Peasants' Revolt broke out in England, during which Gaunt was targeted by the rebels as an especially hated member of the administration.[30] He found himself stranded in the north of England in the early part of the revolt but considered Dunstanburgh insufficiently secure to function as a safe haven, and was forced to turn to Alnwick Castle instead, which refused to let him in, fearing that his presence would invite a rebel attack.[26]

The experience encouraged Gaunt to further expand Dunstanburgh's defences over the next two years.[31] A wide range of work was carried out under the direction of the constable, Thomas of Ilderton, and the mason Henry of Holme, including blocking up the entrance in the gatehouse to turn it into a keep.[32] In 1384 a Scottish army attacked the castle but they lacked siege equipment and were unable to take the defences.[27] Gaunt lost interest in the property after he gave up his role as the Lieutenant of the Marches.[33] Dunstanburgh Castle remained part of the Duchy of Lancaster, but the duchy was annexed to the Crown when Gaunt's son, Henry IV, took the throne of England in 1399.[34]

15th – 16th centuries

[edit]

The Scottish threat persisted, and in 1402 Dunstanburgh Castle's constable, probably accompanied by its garrison, took part in the Battle of Homildon Hill in north Northumberland.[35] Henry VI inherited the throne in 1422 and during the next few decades, numerous repairs were undertaken to the property's buildings and outer defences, which had fallen into disrepair.[36] The Wars of the Roses, a dynastic conflict between the rival houses of Lancaster and York, broke out in the middle of the 15th century.[13] The castle was initially held by the Lancastrians, and the castle's constable, Sir Ralph Babthorpe, died at the Battle of St Albans in 1455, fighting for the Lancastrian Henry VI.[37]

The castle formed part of a sequence of fortifications protecting the eastern route into Scotland, and in 1461 King Edward IV attempted to break the Lancastrian stranglehold on the region.[13] Sir Ralph Percy, one of the joint constables, defended the castle until September 1461, when he surrendered it to the Yorkists.[13] In 1462, Henry VI's wife, Margaret of Anjou, invaded England with a French army, landing at Bamburgh; Percy then switched sides and declared himself for the Lancastrians.[38]

Another Yorkist army was dispatched north in November under the joint command of Richard Neville, 16th Earl of Warwick and John Tiptoft, 1st Earl of Worcester, and Sir Ralph Grey.[39] They besieged the castle, which surrendered that Christmas.[39] Percy was left in charge of Dunstanburgh as part of Edward IV's attempts at reconciliation, but the next year he once again switched sides, returning the castle to the Lancastrians.[40] Percy died at the Battle of Hedgeley Moor in 1464, and the Earl of Warwick reoccupied the castle that June following a short siege.[40]

The castle was probably damaged during the wars, but, other than minor repairs in 1470, nothing was spent on repairs and it fell into disrepair.[41] It was used as a base for piracy in 1470, and by the 1520s its roof was robbed for the lead for use at the castle at Wark-upon-Tweed, and further lead and timber were taken for the moot hall in Embleton.[41] By 1538 it was described in a royal report to Henry VIII as "a very ruinous house and of small strength", and it was observed that only the gatehouse was still habitable.[39] Some repairs were carried out to the walls by Sir William Ellerker, the King's receiver, but a 1543 survey showed it to still be in poor condition.[1]

In 1550 the Warden of the Middle and Eastern Marches, Sir Robert Bowes, described Dunstanburgh as being "in wonderfull great decaye".[1] A report in 1584 suggested that it would cost Queen Elizabeth I £1,000 to restore the castle, but argued that it was too far from the Scottish border to be worth repairing.[42] Alice Craster, a wealthy widow, occupied the castle from 1594 to 1597, probably living in the gatehouse, where she carried out restoration work, and farming the surrounding estate.[43] For much of the 16th century, local farmers bought the right to use the outer bailey of the castle to store their cattle in the event of Scottish raids, at the price of six pence a year.[44]

17th – 19th centuries

[edit]

In 1603, the unification of the Scottish and English crowns eliminated any residual need for Dunstanburgh Castle as a royal fortress.[45] The following year, King James I sold the castle to Sir Thomas Windebank, Thomas Billott and William Blake, who in turn sold it onto Sir Ralph Grey, a nearby landowner, the following year.[46] Ralph's son, William Grey, 1st Baron Grey of Werke, was affirmed as the owner of the castle in 1625.[47]

The Grey dynasty maintained their ownership of the castle, which passed into Lady Mary Grey's side of the family following a law case in 1704.[48] The lands around the castle and the outer bailey were used for growing wheat, barley and oats, and the walls were robbed of their stone for other building work.[49] A small settlement, called Nova Scotia or Novia Scotia, was built on the site of the castle's harbour, possibly by Scottish immigrants.[50] Several engravings were published of the castle in the 18th century, including a somewhat inaccurate depiction by Samuel and Nathaniel Buck in 1720, and by Francis Grose and William Hutchinson in 1773 and 1776 respectively.[51]

Mary's descendants, the Earls of Tankerville, owned the property until the heavily indebted Charles Bennet, 6th Earl of Tankerville, sold it for £155,000 in 1869 to the trustees of the estate of the late Samuel Eyres.[52][nb 2] There had been some attempts at restoration in the early 19th century, and the passageway through the gatehouse was modified and reopened in 1885.[54] The historian Cadwallader John Bates undertook fieldwork at the castle in the 1880s, publishing a comprehensive work in 1891, and a professional architectural plan of the ruins was produced in 1893.[55] Nonetheless, a representative of the estate expressed his concern to the Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle upon Tyne about the condition of the castle in 1898, noting the poor repair of much of the stonework and the importance of the ongoing preservation work that the estate was undertaking.[56]

Dunstanburgh's ruins became a popular subject for artists from the end of the 18th century onwards.[49] Thomas Girtin toured the region and painted the castle, his picture dominated by what art historian Souren Melikian describes as "the forces of nature unleashed", with "wild waves" and dark clouds swirling around the ruins.[57] J. M. W. Turner was influenced by Girtin, and when he first painted the castle in 1797 he similarly focused on the wind and the waves around the ancient ruins, taking some artistic licence with the view of the castle to reinforce its sense of isolated and former grandeur.[58] Turner drew on his visit to produce further works in oils, watercolours, etchings, and sketches, through until the 1830s, making the castle one of the most common subjects in his corpus of work.[59]

A similarly wild view was painted by Thomas Allom showing a ship in a heavy sea offshore, the wreck of which is taken up by Letitia Elizabeth Landon in her poetical illustration to an engraving of that work ![]() Dunstanburgh Castle.[60] published in Fisher's Drawing Room Scrap Book, 1839.

Dunstanburgh Castle.[60] published in Fisher's Drawing Room Scrap Book, 1839.

20th and 21st centuries

[edit]

A golf course was constructed alongside the castle in 1900, and the estate was later sold to Sir Arthur Sutherland, a wealthy shipowner, in 1919.[62] Sutherland opened an additional course at the castle in 1922, designed by the Scottish golfer, James Braid.[63] The costs of maintaining the property became too much for him and, after undertaking eight years of clearance work in the 1920s, he placed the castle into the guardianship of the state in 1930, with the Commissioners of Works taking control of the property.[64] Archaeological investigations were carried out as part of the clearance work by H. Honeyman in 1929, exposing more of the main gatehouse, and further work was carried out under Robert Bosanquet in the 1930s.[65] Aerial photography was carried out by Walter Aitchison for the Ordnance Survey.[66]

Shortly after the outbreak of the Second World War, concerns grew in the British government about the threat of German invasion along the east coast of England.[67] The bays just to the north of Dunstanburgh Castle were vulnerable targets for an enemy amphibious landing, and efforts were made to fortify the castle and the surrounding area in 1940, as part of a wider line of defences erected by Sir Edmund Ironside.[68]

The castle itself was occupied by a unit of the Royal Armoured Corps, who served as observers; the soldiers appear to have relied on the stone walls for protection rather than trenches, and, unusually, no additional firing points were cut out of the stonework, as typically happened elsewhere.[69] The surrounding beaches were defended with lines of barbed wire, slit trenches and square weapons pits, reinforced by concrete pillboxes to the north and south of the castle, at least partially laid down by the 1st Battalion Essex Regiment.[70]

A 20-foot (6.1 m) wide ditch was dug at the north end of the moat to prevent tanks from breaking through and following the track south past the castle, and a 545-by-151-foot (166 by 46 m) wide anti-personnel minefield was laid to the south-west to prevent infantry soldiers from circumventing the castle's defences and advancing down into Craster.[71] After the end of the war, the barbed wire was cleared away from the beaches by local Italian prisoners of war, although the two pillboxes, the remnants of the anti-tank ditch and some of the trenches and weapons pits remain.[72]

In 1961, Arthur's son, Sir Ivan Sutherland, passed the estate to the National Trust.[73] Archaeological surveys were carried out in 1985, 1986 and 1989 by Durham University, and between 2003 and 2006 researchers from English Heritage carried a major archaeological investigation of 35 hectares (86 acres) of land around the castle.[74]

In the 21st century, the castle remains owned by the National Trust and is managed by English Heritage.[75] The site is a Scheduled Ancient Monument and the ruins are protected under UK law as a Grade I listed building.[76] It lies within the Northumberland Coast Area of Outstanding Natural Beauty, and is part of a Site of Special Scientific Interest, with parts of the site comprising a Special Protection Area for the conservation of wild birds.[77] The National Trust has encouraged the land around the outside of the castle to remain waterlogged to enable the conservation of amphibians and bird species, and the inside of the castle is protected from grazing animals to encourage nesting birds.[78]

Architecture and landscape

[edit]Landscape

[edit]

Dunstanburgh Castle occupies a 68-acre (28-hectare) site within a larger 610-acre (250-hectare) body of National Trust land along the coast.[79] The castle is situated on a prominent headland, part of the Great Whin Sill geological formation.[80] On the south side of the castle there is a gentle slope across low-lying, boggy ground, but along the northern side, the Gull Crag cliffs form a natural barrier up to 30-metre (98 ft) high.[81] The cliffs are punctuated by various defiles, formed from weaknesses in the black basalt rock, including the famous Rumble Churn.[80]

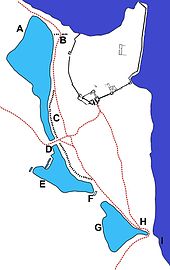

The landscape around the castle was carefully designed in the 14th century as a deer park or planned borough, and would have looked similar to those at the contemporary castles of Framlingham, Kenilworth, Leeds and Whittington; in particular, Kenilworth may have been a specific model for Dunstanburgh.[82] The area around the castle was dominated by three shallow artificial lakes, called meres, and accessed by three gates on the north, west and south sides.[83][nb 3] The meres were fed from a freshwater spring 2,000 feet (610 m) inland, linked to the meres by an underground stone channel.[85] The meres were originally bounded by a sod-cast boundary bank and ditch; today this is heavily eroded, and up to 3-foot-3-inch (0.99 m) high.[83] The main route by land into the castle would have been from the village of Embleton, through the West Gate.[86]

The North Mere is 5.6 acres (2.3 hectares) in area, and is blocked off on its northern end by a sod-cast bank, adjacent to the site of the North Gate.[87] The southern half takes the form of a 331-foot (101 m) long moat, which was recorded as being 18 feet (5.5 m) deep in the medieval period, terminating in the West Gate.[88] The northern part of this mere occasionally floods in the 21st century, creating a temporary lake, and the moated section usually still contains some standing water.[89] The West Mere, covering 2.25 acres (0.91 hectares), stretches away from the location of West Gate and is blocked at the far end by a small, stone dam.[90] Three rectangular fishponds were built alongside the West Mere, the smallest, probably a stew pond for raising young fish, being fed with water from the lake.[91] A protective earthen bank, probably originally reinforced by a timber palisade, ran for approximately 490 feet (150 m) along either side of the West Gate, where a gatehouse was probably built.[92] At the far end of the lake complex was the South Mere, 2.25 acres (0.91 hectares) in size, with the South Gate positioned in its eastern corner.[83]

A harbour was built south-east of the castle, which would originally have been used to receive first building materials, then later senior members of the castle household or important guests.[93] All that remains of the harbour is its 246-foot (75 m) quay, built from basalt boulders, and it may not have been in frequent use during the medieval period, since it could only have been safely used during periods of good weather.[94] West of the castle is a later shieling, the earthwork remains of a longhouse.[95] South of this is a rectangular earthwork, with walls over 3 feet 3 inches (0.99 m) high, which may have been a siege fortification from 1462.[96] If this is such siege work, it would be a unique survival in England from this period.[95]

Architecture

[edit]

Dunstanburgh Castle's buildings are located around the outside of the fortification's outer bailey, enclosed by a stone curtain wall, which enclose 9.96 acres (4.03 ha), making it the largest castle in Northumberland.[97] Possibly from the very start of the castle, and certainly by the 1380s, the castle buildings formed three distinct complexes supporting the Earl's household, the castle's constable and the administration of the Embleton barony respectively.[98] The inside of the bailey still shows the marks of former strip farming, which can be seen in winter.[93]

The southern and western parts of the walls were originally faced with a local ashlar sandstone with a core of basalt rubble; the sandstone was mostly quarried at Howick.[99] The sandstone has since been stripped from the western parts of the wall, and the sandstone along the eastern end of the walls gives way to small limestone blocks, originally only laid 11 feet (3.4 m) high with a 4-foot-11-inch (1.50 m) parapet, but later raised in height with additional basalt boulders, probably during the Wars of the Roses.[100] It is uncertain if the curtain wall originally extended above the cliffs along the northern edge of the castle.[101][nb 4]

Moving anticlockwise around the curtain wall from the north-west, the rectangular Lilburn Tower looks out across Embleton beach.[103] The tower was named after an early castle constable, John de Lilburn, but may have been built under Thomas of Lancaster; it was intended as a high-status residence, 59 feet (18 m) high, 30 feet (9.1 m) square with 6-foot (1.8 m) thick walls, with a guardroom for soldiers on the ground floor.[104] The rectangular towers at Dunstanburgh reflects the local tradition in Northumberland, and are similar to those at nearby Alnwick.[105] Further along the wall there are the remains of a small tower, called Huggam's House by local tradition.[106] Earthworks around the inside of the curtain wall suggest that there may once have been a complex of buildings stretching between Lilburn Tower and Huggam's House.[106]

On the southwest corner of the walls are the castle gatehouses. The most prominent of these is the Great Gatehouse, a massive three-storey fortification, comprising two drum-shaped towers of ashlar stone; originally 79 feet (24 m) high.[107] This was heavily influenced by the Edwardian gatehouses in North Wales, such as that at Harlech, but contains unique features, such as the frontal towers, and is considered by historians Alastair Oswald and Jeremy Ashbee to be "one of the most imposing structures in any English castle".[108] In the 1380s this gatehouse was further strengthened with a 31-foot (9.4 m) long barbican, of which only the rubble foundations now survive, around 2 feet 4 inches (0.71 m) high.[109]

The passageway through the gatehouse was protected by a portcullis and possibly a set of wooden gates.[110] The ground floor contained two guardrooms, each 21-foot (6.4 m) wide, and latrines, with spiral staircases in the corner of the gatehouse running up to the first floor, where relatively well-lit chambers with fireplaces probably accommodated the garrison's officers.[111] The staircases continued up to the second floor, containing the castle's great hall, an antechamber, and bedchamber, originally intended for the use of Thomas of Lancaster and his family.[112] Four towers extended above the gatehouse's lead-covered roof for an additional two storeys of height, giving extensive views of the surrounding area.[113] This design may have influenced the construction of Henry IV's gatehouse at Lancaster Castle.[114]

Immediately to the west of the Great Gatehouse is John of Gaunt's Gatehouse, originally either two or three storeys tall, but now only surviving at the foundation level.[115] This gatehouse replaced the Great Gatehouse as the main entrance, and would have contained a porter's lodge, defended by a combination of a portcullis and an 82-foot (25 m) long barbican.[116] A inner bailey was approximately 50 by 75 feet (15 by 23 m), defended by a 20-foot (6.1 m) high mantlet wall, was constructed in the 1380s behind John of Gaunt's Gatehouse and the Great Gatehouse.[117] This complex comprised a vaulted inner gatehouse, 30-foot (9.1 m) square, and six buildings, including an antechamber, kitchen and bakehouse.[118]

Further along, the south side of the walls is the Constable's Tower, a square tower containing comfortable accommodation for the castle's constable, including stone window seats.[119] On the inside of the walls are the foundations of a hall and chamber, built before 1351, part of a larger complex of buildings used by the constable and his household, approximately 60-foot (18 m) square.[120] To the west of the Constable's Tower is a small turret that projects from the upper wall – an unusual feature, similar to that at Pickering Castle – and a mural garderobe; and to the east a small oblong turret with a single chamber, 10.75 by 7.5 feet (3.28 by 2.29 m).[121]

In the south-east corner of the walls, the Egyncleugh Tower – whose name means "eagle's ravine" in the Northumbrian dialect – overlooks Queen Margaret's Cove below.[122][nb 5] A three-storey, square building, 25-foot (7.6 m) across, Egyncleugh Tower was designed to house a castle official, and included a small gateway and drawbridge into the castle, either for the use of the castle constable, or possibly for the local people.[124]

There is a postern gate in the eastern wall, added in the 1450s, and a further gateway in the north-eastern corner, which gave access to Castle Point and Gull Crag below.[125] Along the inside of the curtain walls are the foundations of a yard, 200 by 100 feet (61 by 30 m), and a large rectangular building, usually identified as a grange or a barn.[126] This would have probably supported the administration of the Embleton estates, and have included the auditor's chamber and other facilities.[98]

Interpretation

[edit]

Early analysis of Dunstanburgh Castle focused on its qualities as a military, and a defensive site, but more recent work has emphasised the symbolic aspects of its design and the surrounding landscape.[127] Although the castle was intended as a secure bolt-hole for Thomas of Lancaster should events go awry in the south of England, it was, however "clearly not an inconspicuous hiding place", as the English Heritage research team have pointed out: it was a spectacular construction, located in the centre of a huge, carefully designed medieval landscape.[128] The meres surrounding the castle would have reflected the castle walls and towers, turning the outcrop into a virtual island and producing what the historians Oswald and Ashbee have called "an awe-inspiring and beautiful sight".[129]

The different elements of the castle were also positioned for a particular effect. Unusually, the huge Great Gatehouse faced southeast, away from the main road, hiding its extraordinary architectural features.[130] This may have been because Thomas intended to establish a new settlement in front of it, but the gatehouse was also probably intended to be viewed from the harbour, where the most senior visitors were expected to arrive.[131] The Lilburn Tower was positioned to be clearly – and provocatively – visible to Edward II's castle at Bamburgh, 9 miles (14 km) away along the coast, and would have been elegantly framed by the entranceway to the Great Gatehouse for any visitors.[132] It was also positioned on a set of natural basalt pillars, which – although inconvenient to build upon – would have enhanced its dramatic appearance and reflection in the meres.[133]

The design of the castle may also have alluded to Arthurian mythology, which was a popular set of ideals and beliefs among the English ruling classes at the time.[134] Thomas appears to have had an interest in the Arthurian legends and used the pseudonym "King Arthur" in his correspondence with the Scots.[135] Dunstanburgh, with an ancient fort at its centre encircled by water, may have been an allusion to Camelot, and in turn to Thomas's claim to political authority over the failing Edward II, and was also strikingly similar to contemporary depictions of Sir Lancelot's castle of "Joyous Garde".[136]

Folklore

[edit]

Sir Guy the Seeker

Dunstanburgh Castle has been closely associated with the legend of Sir Guy the Seeker since at least the early 19th century.[137] Different versions of the story vary slightly in their details, but typically involve a knight, Sir Guy, arriving at Dunstanburgh Castle, where he was met by a wizard and led inside.[137] There he comes across a noble lady imprisoned inside a crystal tomb and guarded by a sleeping army.[137] The wizard offers Guy a choice of either a sword or a hunting horn to help free the lady; he incorrectly chooses the horn, which wakes the sleeping knights.[137] Sir Guy finds himself outside Dunstanburgh Castle and spends the rest of his life attempting to find a way back inside.[137]

It is unclear when the story first emerged, but similar stories, possibly inspired by medieval Arthurian legends, exist at the nearby locations of Hexham and the Eildon Hills.[138] Matthew Lewis wrote a poem, Sir Guy the Seeker, popularising the story in 1808, with subsequent versions produced by W. G. Thompson in 1821 and James Service in 1822.[139] The tale continues to be told as part of the local oral tradition.[137]

Several other oral traditions about the castle survive.[140] One of these involves a child prisoner within the castle, who escaped, throwing the key to her dungeon into a nearby field, sometimes argued to be an outcrop of land north-west of the castle, which from then onwards was infertile.[140] Another centres on a man called Gallon who was left in charge of the castle by Margaret of Anjou and entrusted with a set of valuables; captured by the Yorkists, he escaped and later returned to reclaim six Venetian glasses.[140] The historian Katrina Porteous has noted that in the 14th century there are records of receivers and bailiffs at the castle called Galoun, potentially linked to the origins of the Gallon of this story.[140]

There are local stories of tunnels stretching from Dunstanburgh Castle to Craster Tower, Embleton, and nearby Proctor Steads, as well as a tunnel running from the castle well to the west of the castle.[140] These stories may be linked to the presence of the drainage system around the castle.[141]

See also

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ It is impossible to accurately compare 14th-century and modern prices or incomes. For comparison, £184 represents about a third of the yearly income of a typical nobleman such as Richard le Scrope, whose lands brought in around £600 a year.[18]

- ^ £155,000 in 1869 would be worth between £13 million and £244 million in 2013 terms, depending on the financial measure used.[53]

- ^ Earlier scholarship had suggested that the meres were originally saltwater inlets, linked by the moat of the north mere, and connected to the sea at either end. The 2003 investigations at the site comprehensively disproved this theory, showing the meres to have always been freshwater lakes.[84]

- ^ There are historical references in 1543 to a former wall running along the north side of the castle, but it was already being described as having been eroded by the sea many years before, and the assertion that it originally existed may not be authoritative. It is also uncertain whether this statement referred to a defensive curtain wall, of which no trace remains, or a simpler wall to protect livestock. Some erosion of the cliffs has occurred since the castle was first built, but little has occurred since 1861 and it is far from certain that sufficient erosion would have taken place to have destroyed any original walls.[102]

- ^ The Egyncleugh Tower was also called the Margaret Tower for a period, after Queen Margaret's Cove below.[123]

References

[edit]- ^ a b c Blair & Honeyman 1955, pp. 10–11

- ^ a b Oswald & Ashbee 2011, p. 5

- ^ a b Oswald & Ashbee 2011, p. 25

- ^ a b Oswald & Ashbee 2011, p. 25; "Prehistory", English Heritage, retrieved 23 August 2014

- ^ a b Oswald et al. 2006, p. 17

- ^ Oswald & Ashbee 2011, p. 25; Oswald et al. 2006, p. 17; "Prehistory", English Heritage, retrieved 23 August 2014

- ^ Oswald & Ashbee 2011, pp. 27, 29

- ^ Prestwich 2003, pp. 75–76

- ^ a b Oswald et al. 2006, p. 92

- ^ Oswald et al. 2006, p. 17; Oswald & Ashbee 2011, p. 27; "Research on Dunstanburgh Castle", English Heritage, retrieved 23 August 2014

- ^ Prestwich 2003, pp. 76–79; Oswald & Ashbee 2011, p. 25; Oswald et al. 2006, p. 93; "Constructing the Castle at Dunstanburgh", English Heritage, retrieved 23 August 2014

- ^ Oswald & Ashbee 2011, p. 25; Oswald et al. 2006, p. 93; "Constructing the Castle at Dunstanburgh", English Heritage, retrieved 23 August 2014

- ^ a b c d Oswald & Ashbee 2011, p. 33

- ^ Oswald et al. 2006, pp. 17–18

- ^ Oswald & Ashbee 2011, p. 16

- ^ a b c Oswald et al. 2006, p. 18

- ^ a b Oswald & Ashbee 2011, p. 27

- ^ Given-Wilson 1996, p. 157

- ^ Oswald et al. 2006, p. 18; Oswald & Ashbee 2011, p. 33

- ^ King 2003, pp. 115, 128; Oswald et al. 2006, p. 97

- ^ a b Oswald & Ashbee 2011, p. 29

- ^ Blair & Honeyman 1955, p. 6 for merchant bit

- ^ Oswald & Ashbee 2011, p. 30; Cornell 2006, p. 108

- ^ Cornell 2006, pp. 8–9, 20–21, 260

- ^ Oswald & Ashbee 2011, p. 27; Cornell 2006, p. 108

- ^ a b c Oswald & Ashbee 2011, p. 30

- ^ a b Blair & Honeyman 1955, p. 8

- ^ Oswald & Ashbee 2011, p. 30; Blair & Honeyman 1955, p. 8

- ^ Middleton & Hardie 2009, p. 45

- ^ Dunn 2002, pp. 67, 79

- ^ Oswald & Ashbee 2011, pp. 30, 32

- ^ Oswald & Ashbee 2011, pp. 30, 32; Blair & Honeyman 1955, p. 8

- ^ Middleton & Hardie 2009, p. 22

- ^ Oswald & Ashbee 2011, p. 32

- ^ Cornell 2006, p. 258

- ^ Oswald & Ashbee 2011, p. 32; Blair & Honeyman 1955, pp. 8–9

- ^ Oswald & Ashbee 2011, p. 33; Blair & Honeyman 1955, p. 9

- ^ Oswald & Ashbee 2011, pp. 33–34

- ^ a b c Oswald & Ashbee 2011, p. 34

- ^ a b Blair & Honeyman 1955, p. 10; Middleton & Hardie 2009, p. 22

- ^ a b Oswald & Ashbee 2011, p. 34; Blair & Honeyman 1955, p. 10; Middleton & Hardie 2009, p. 22

- ^ Oswald & Ashbee 2011, p. 35; Blair & Honeyman 1955, p. 11

- ^ Oswald & Ashbee 2011, p. 35; Middleton & Hardie 2009, p. 24

- ^ Middleton & Hardie 2009, pp. 23–24

- ^ Oswald & Ashbee 2011, p. 35

- ^ Oswald et al. 2006, p. 20; "The Wars of the Roses", English Heritage, retrieved 23 August 2014

- ^ Tate 1869–72, p. 91; Bates 1891, p. 187; "Estate records of the Earls Grey and Lords Howick", Durham University, retrieved 23 August 2014

- ^ Oswald et al. 2006, p. 20; Tate 1869–72, pp. 91–92

- ^ a b Oswald & Ashbee 2011, p. 36

- ^ Middleton & Hardie 2009, p. 25

- ^ Oswald et al. 2006, p. 9

- ^ Oswald et al. 2006, p. 20; Tate 1869–72, p. 92; "Estate records of the Earls Grey and Lords Howick", Durham University, retrieved 23 August 2014

- ^ Lawrence H. Officer; Samuel H. Williamson (2014), "Five Ways to Compute the Relative Value of a UK Pound Amount, 1270 to Present", MeasuringWorth, archived from the original on 26 August 2014, retrieved 23 August 2014

- ^ Oswald & Ashbee 2011, p. 37; "List Entry", Historic England, retrieved 6 July 2015

- ^ Oswald et al. 2006, pp. 9–10

- ^ The Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle-upon-Tyne 1898, pp. 113–114

- ^ Matthew Imms (2008), J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, ISBN 9781849763868, retrieved 23 August 2014

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); Souren Melikian (2002), "London Exhibition : A Draftsman's Sense, an Artist's Sensibility", The New York Times, retrieved 23 August 2014 - ^ Bryant 1996, p. 64; Sarah Richardson (2012), "JMW Turner's 'Dunstanburgh Castle': poetry, imagination and reality", Tyne and Wear Museums, retrieved 23 August 2014; "Research on Dunstanburgh Castle", English Heritage, retrieved 23 August 2014; Matthew Imms (2008), J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, ISBN 9781849763868, retrieved 23 August 2014

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Matthew Imms (2008), J.M.W. Turner: Sketchbooks, Drawings and Watercolours, ISBN 9781849763868, retrieved 23 August 2014

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help); Middleton & Hardie 2009, p. 69 - ^ Landon, Letitia Elizabeth (1838). "picture". Fisher's Drawing Room Scrap Book, 1839. Fisher, Son & Co.Landon, Letitia Elizabeth (1838). "poetical illustration". Fisher's Drawing Room Scrap Book, 1839. Fisher, Son & Co.

- ^ Middleton & Hardie 2009, p. 53

- ^ Oswald et al. 2006, p. 20; Middleton & Hardie 2009, pp. 33–34

- ^ Oswald et al. 2006, p. 20; Middleton & Hardie 2009, p. 34

- ^ Oswald & Ashbee 2011, p. 37; Oswald et al. 2006, pp. 11, 20; Blair & Honeyman 1955, p. 11; "Into the 20th century", English Heritage, retrieved 23 August 2014

- ^ Oswald et al. 2006, p. 13

- ^ Oswald et al. 2006, p. 15

- ^ Oswald et al. 2006, p. 87

- ^ Oswald et al. 2006, p. 87; Middleton & Hardie 2009, p. 52

- ^ Oswald et al. 2006, pp. 87, 89; "Into the 20th century", English Heritage, retrieved 23 August 2014

- ^ Oswald et al. 2006, pp. 87, 89

- ^ Oswald et al. 2006, pp. 89–90; Middleton & Hardie 2009, p. 53

- ^ Oswald et al. 2006, pp. 87, 89–90; Middleton & Hardie 2009, pp. 56, 58

- ^ "Acquisitions up to 2011: An Historical Summary of Trust Acquisitions (Including Covenants)", The National Trust, p. 101, archived from the original on 14 July 2014, retrieved 23 August 2014

- ^ Middleton & Hardie 2009, p. 5; Oswald et al. 2006, p. 16

- ^ Middleton & Hardie 2009, p. 5

- ^ Middleton & Hardie 2009, p. 7

- ^ Middleton & Hardie 2009, pp. 7–8

- ^ Oswald et al. 2006, pp. 4–5

- ^ Middleton & Hardie 2009, pp. 4, 7

- ^ a b Oswald et al. 2006, p. 4

- ^ Oswald & Ashbee 2011, p. 17; Oswald et al. 2006, p. 4

- ^ Middleton & Hardie 2009, p. 42; Oswald et al. 2006, pp. 93, 95

- ^ a b c Middleton & Hardie 2009, p. 44

- ^ Oswald et al. 2006, pp. 65, 73

- ^ Oswald et al. 2006, p. 65

- ^ Oswald et al. 2006, p. 34

- ^ Middleton & Hardie 2009, p. 43

- ^ Oswald & Ashbee 2011, p. 22; Middleton & Hardie 2009, p. 43; Oswald et al. 2006, p. 70

- ^ Oswald & Ashbee 2011, pp. 22, 40

- ^ Middleton & Hardie 2009, p. 43; Oswald & Ashbee 2011, p. 22; Oswald et al. 2006, p. 70

- ^ Middleton & Hardie 2009, pp. 43–44; Oswald et al. 2006, p. 71

- ^ Oswald & Ashbee 2011, p. 22; Oswald et al. 2006, p. 64

- ^ a b Oswald & Ashbee 2011, p. 12

- ^ Oswald & Ashbee 2011, p. 12; Oswald et al. 2006, p. 80

- ^ a b Middleton & Hardie 2009, p. 48

- ^ Middleton & Hardie 2009, pp. 48–49

- ^ Oswald et al. 2006, p. 61; Oswald et al. 2006, p. 96

- ^ a b Oswald et al. 2006, p. 96

- ^ Oswald & Ashbee 2011, pp. 5, 15–16, 19; Middleton & Hardie 2009, p. 13

- ^ Oswald & Ashbee 2011, pp. 5, 15–16, 19; Oswald et al. 2006, p. 60

- ^ Oswald & Ashbee 2011, p. 17

- ^ Oswald et al. 2006, p. 60

- ^ Oswald & Ashbee 2011, p. 18

- ^ Oswald & Ashbee 2011, p. 18; Blair & Honeyman 1955, p. 17; Oswald et al. 2006, p. 55

- ^ "Significance of Dunstanburgh Castle", English Heritage, retrieved 23 August 2014; "Research on Dunstanburgh Castle", English Heritage, retrieved 23 August 2014

- ^ a b Oswald & Ashbee 2011, p. 19

- ^ Oswald & Ashbee 2011, pp. 5, 7, 10; Blair & Honeyman 1955, p. 16; Goodall 2011, p. 249

- ^ Oswald & Ashbee 2011, pp. 5, 7; "Significance of Dunstanburgh Castle", English Heritage, retrieved 23 August 2014

- ^ Oswald & Ashbee 2011, p. 5; Blair & Honeyman 1955, p. 14; Oswald et al. 2006, pp. 40–41

- ^ Oswald & Ashbee 2011, p. 6

- ^ Oswald & Ashbee 2011, pp. 6–8; Blair & Honeyman 1955, p. 15

- ^ Oswald & Ashbee 2011, pp. 8–10

- ^ Oswald & Ashbee 2011, pp. 5, 9–10

- ^ Goodall 2011, p. 342

- ^ Oswald & Ashbee 2011, pp. 19–20

- ^ Oswald & Ashbee 2011, p. 20; Blair & Honeyman 1955, p. 14; Oswald et al. 2006, p. 51

- ^ Oswald & Ashbee 2011, p. 20; Blair & Honeyman 1955, p. 16

- ^ Oswald & Ashbee 2011, pp. 20–21; Blair & Honeyman 1955, p. 16

- ^ Oswald & Ashbee 2011, p. 14

- ^ Oswald & Ashbee 2011, p. 14; Blair & Honeyman 1955, p. 20

- ^ Blair & Honeyman 1955, pp. 20–21; Goodall 2011, pp. 249, 453

- ^ Oswald & Ashbee 2011, p. 15

- ^ Oswald et al. 2006, p. 54

- ^ Oswald & Ashbee 2011, p. 15; Blair & Honeyman 1955, p. 20; Oswald et al. 2006, p. 55

- ^ Oswald & Ashbee 2011, pp. 15, 17

- ^ Oswald & Ashbee 2011, pp. 16–17; Blair & Honeyman 1955, p. 18

- ^ Oswald et al. 2006, pp. 92–93

- ^ Oswald et al. 2006, p. 93; Oswald & Ashbee 2011, pp. 22–23

- ^ Oswald & Ashbee 2011, p. 23; Middleton & Hardie 2009, p. 20

- ^ Oswald et al. 2006, p. 96; Oswald & Ashbee 2011, pp. 13, 22

- ^ Oswald et al. 2006, p. 96; Oswald & Ashbee 2011, p. 13

- ^ Oswald et al. 2006, pp. 55–56

- ^ Oswald et al. 2006, pp. 57–58

- ^ Oswald et al. 2006, pp. 93–94

- ^ Oswald & Ashbee 2011, p. 28

- ^ Oswald et al. 2006, pp. 93–94; Oswald & Ashbee 2011, pp. 23, 28

- ^ a b c d e f Oswald et al. 2006, p. 21

- ^ Oswald et al. 2006, pp. 24–25

- ^ Oswald et al. 2006, pp. 21–22

- ^ a b c d e Oswald et al. 2006, p. 27

- ^ Oswald et al. 2006, pp. 27–28

Bibliography

[edit]- Bates, C. J. (1891). "Border Holds of Northumberland" (PDF). Archaeologia Aeliana. 14: 167–194.

- Blair, C. H.; Honeyman, H. L. (1955). Dunstanburgh Castle, Northumberland (2nd ed.). London, UK: Her Majesty's Stationery Office. OCLC 30169286.

- Bryant, Julius (1996). Turner: Painting the Nation. London, UK: English Heritage. ISBN 9781850746546.

- Cornell, David (2006). English Castle Garrisons in the Anglo-Scottish Wars of the Fourteenth Century (PhD). Durham, UK: Durham University.

- Dunn, Alastair (2002). The Great Rising of 1381: The Peasants' Revolt and England's Failed Revolution. Stroud, UK: Tempus. ISBN 9780752423234.

- Given-Wilson, Chris (1996). The English Nobility in the Late Middle Ages. London, UK: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-44126-8.

- Goodall, John (2011). The English Castle. New Haven, US, and London, UK: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300110586.

- King, Andy (2003). "Bandits, Robbers and Schavaldours: War and Disorder in Northumberland in the Reign of Edward II". In Prestwich, M.; Britnell, R.; Frame, R. (eds.). Thirteenth Century England. Vol. 9. Woodbridge, UK: Boydell. pp. 115–130.

- Middleton, Penny; Hardie, Caroline (2009). Historic Environment Survey for the National Trust Properties on the Northumberland Coast: Dunstanburgh and Embleton Bay, Report No: 0058/4-09. Barnard Castle, UK: Archaeo-Environment.

- Oswald, Alastair; Ashbee, Jeremy (2011). Dunstanburgh Castle. London, UK: English Heritage. ISBN 9781905624959.

- Oswald, Alastair; Ashbee, Jeremy; Porteous, Katrina; Huntley, Jacqui (2006). Dunstanburgh Castle, Northumberland: Archaeological, Architectural and Historical Investigations (PDF). London, UK: English Heritage. ISSN 1749-8775. Archived from the original (PDF) on 13 September 2014. Retrieved 13 September 2014.

- Prestwich, Michael (2003). The Three Edwards: War and State in England, 1272–1377 (2nd ed.). London, UK and New York City: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-30309-5.

- The Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle-upon-Tyne (1898). "Dunstanburgh Castle". Proceedings of the Society of Antiquaries of Newcastle-upon-Tyne. 8 (14): 113–114.

- Tate, G. (1869–72). "Dunstanburgh Castle". History of the Berwickshire Naturalist Club. 6: 85–94.