West Virginia University

{{Infobox university

| name = West Virginia University | image = West Virginia University seal.svg | image_upright = 0.7 | latin_name = Collegium (Universitas) Occidentalis Virginia | former_name = Agricultural College of West Virginia (1867–1868)[1] | motto = Πίστει τὴν ἀρετήν, ἐν δὲ τῇ ἀρετῇ τὴν γνῶσιν (Koine Greek) | mottoeng = "Add to your faith virtue; and to virtue, knowledge" (2 Peter 1:5 KJV) | established = February 7, 1867 | type = Public land-grant research university

| academic_affiliations =

- CONAHEC

- WVHEPC

- Space-grant

| endowment = $843.62 million (2023)[2] | administrative_staff = 7,566 | faculty = 1,870 | president = E. Gordon Gee[3] | provost = Maryanne Reed[4] | students = 24,200 (fall 2023)[5] | undergrad = 18,616 (fall 2023)[5] | postgrad = 5,584 (fall 2023)[5] | city = Morgantown | state = West Virginia | country = United States | coordinates = 39°38′45″N 79°58′11″W / 39.6458°N 79.9697°W | campus = Small city[6] | campus_size = 1,892 acres (7.66 km2) | colors = Old Gold and Blue[7]

| mascot = The Mountaineer | nickname = Mountaineers

| sporting_affiliations =

| website = www.wvu .edu | logo = West Virginia University logo.svg | logo_upright = 1.0 | accreditation = HLC | free_label2 = Newspaper | free2 = The Daily Athenaeum | free_label = Other campuses | free = {{hlist|Beckley|Bridgeport|Charleston|Keyser|Martinsburg

West Virginia University (WVU) is a public land-grant research university with its main campus in Morgantown, West Virginia, United States. Its other campuses are those of the West Virginia University Institute of Technology in Beckley, Potomac State College of West Virginia University in Keyser, and clinical campuses for the university's medical school at the Charleston Area Medical Center and Eastern Campus in Martinsburg. WVU Extension Service provides outreach with offices in all 55 West Virginia counties.

Enrollment for the fall 2023 semester was 24,200 for the main campus, while enrollment across all three non-clinical campuses was 26,791.[5] The Morgantown campus offers more than 350 bachelor's, master's, doctoral, and professional degree programs throughout 13 colleges and schools, including that state's only law and dental schools.[8] Faculty and alumni include 25 Truman Scholars, 47 Goldwater Scholars, 88 Gilman Scholars, 70 Fulbright Scholars, and 25 Rhodes Scholars.[8]

History

[edit]

Establishment

[edit]Under the terms of the 1862 Morrill Land-Grant Colleges Act, the West Virginia Legislature created the Agricultural College of West Virginia on February 7, 1867, and the school officially opened on September 2 of the same year.[9][10] On December 4, 1868, lawmakers renamed the college West Virginia University to represent a broader range of higher education.[11] It built on the grounds of three former academies, the Monongalia Academy of 1814, the Morgantown Female Academy of 1831, and Woodburn Female Seminary of 1858.[12] Upon its founding, the local newspaper claimed that "a place more eligible for the quiet and successful pursuit of science and literature is nowhere to be found".[10]

The first campus building was constructed in 1870 as University Hall and was renamed Martin Hall in 1889 in honor of West Virginia University's first president, the Rev. Alexander Martin of Scotland.[13] After a fire destroyed the Woodburn Seminary building in 1873, the centerpiece of what is now Woodburn Hall was completed in 1876, under the name New Hall. The name was changed to University Building in 1878 when the College of Law was founded as the first professional school in the state of West Virginia.[14] The precursor to Woodburn Circle was finished in 1893 when Chitwood Hall (then Science Hall) was constructed on the bluff's north side. In 1909 a north wing was added to University Building, and the facility was renamed Woodburn Hall. Throughout the next decade, Woodburn Hall underwent several renovations and additions, including the construction of the south wing and east tower (in 1930) housing the Seth Thomas clock.[15] The three Woodburn Circle buildings were listed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1974.[16][17] In 1899, the Vance Farm was acquired for the West Virginia University Experiment Station. The Reymann Memorial Farm was given to West Virginia University in 1917 by the family of Anton Reymann of Wheeling in memory of Lawrence A. Reymann. The farm consisting of 990 acres located in Wardensville in Hardy County, comes until the Davis College of Agriculture.[18]

WVU was required to have a Cadet Corps under the terms of the Morrill Act of 1862, which allowed for the creation of land-grant colleges. The United States Department of War—a predecessor of the U.S. Department of Defense—offered military equipment to the university at no charge, forming the basis of the school's Military Tactics department. The heavy military influence led to opposition of female enrollment that lasted through the first decade of the university.[19] The trend changed in 1889 when ten women were allowed to enroll and seek degrees at the university. In June 1891, Harriet Lyon became the first (white) woman to receive a degree from West Virginia University, finishing first in the class ahead of all male students.[19] Lyon's academic success supported the acceptance of women in the university as students and educators.[20]

During the university's early years, daily chapel services and roll call for all students were mandatory, limiting time for student recreation. Following the removal of these obligations, students became active in extracurricular activities and established many of the school's first athletic and student organizations. The first edition of the student newspaper known as the Athenaeum, now The Daily Athenaeum, was published in 1887, and the West Virginia Law Review became the fourth-oldest law review in the United States when it was founded in 1894. In 1897, E. Eva Hubbard (1858–1947) became the first head of WVU's new Department of Art.[21] Of Hubbard's students was renowned Modernist Blanche Lazzell.[21] Phi Kappa Psi was the first fraternity on campus, founded May 23, 1890, while Kappa Delta, the first sorority at WVU, was established in 1899.[19] The first football team was formed in 1891, and the first basketball team appeared in 1903.[22]

Early 20th century

[edit]

The university's outlook at the turn of the 20th century was optimistic, as the school constructed the first library in present-day Stewart Hall in 1902.[23]

The campus welcomed U.S. President William Howard Taft to the campus for WVU President Thomas Hodges's inauguration in 1911.[19] On November 2, 1911, President Taft delivered the address "World Wide Speech", from the front porch of Purinton House.[24] However, the university's efforts to attract more qualified educators, increase enrollment, and expand the campus was hindered during a period that saw two World Wars and the Great Depression. With a heavy military influence in the university, many students left college to join the army during World War I, and the local ROTC was organized in 1916.[25] Women's involvement in the war efforts at home led to the creation of Women's Hall dormitory, now Stalnaker Hall, in 1918.[26]

Despite its wartime struggles, the university established programs in biology, medicine, journalism, pharmacy, and the first mining program in the nation. In 1918, Oglebay Hall was built to house the expanded agriculture and forestry programs.[25] Additionally, the first dedicated sports facilities were constructed including "The Ark" for basketball in 1918, and the original Mountaineer Field in 1925. Stansbury Hall was built in 1928 and included a new basketball arena named "The Fieldhouse" that held 6,000 spectators.[27] Elizabeth Moore Hall, the woman's physical education building, was also completed in 1928.[28] Men's Hall, the first dormitory built for men on campus, was built in 1935 and was funded in part by the Works Progress Administration.[29] The Mountaineer mascot (based on the mountain man) was adopted during the late 1920s, with an unofficial process to select the Mountaineer through 1936. An official selection process began naming the mascot annually in 1937, with Boyd "Slim" Arnold becoming the first Mountaineer to wear the buckskin uniform.[30]

As male students left for World War II in 1941–42, women became more prominent in the university and surpassed the number of males on campus for the first time in 1943.[19] Soldiers returning from the war qualified for the G.I. Bill and helped increase enrollment to over 8,000 students for the first time, but the university's facilities were becoming inadequate to accommodate the surging student population.

Campus expansion

[edit]

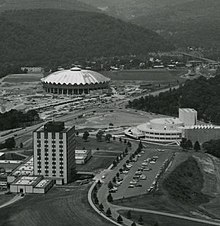

Preparation for the baby boomer generation and plans for curriculum expansion led to the purchase of land for the Evansdale and Medical campuses. The growth of downtown Morgantown limited the space available on the original campus; therefore, the new site was nearly two miles north on what had been farmland.[19] Beginning in the late 1950s the university experienced the most rapid period of growth in its history. In 1957, WVU opened a Medical Center on the new campus and founded the first school of dentistry in West Virginia. The basketball program reached a new level of success when the university admitted future 14‑time NBA All-Star and Hall of Fame player Jerry West, who led the team to the national championship game in 1959.[31] As enrollment approached 14,000 in the 1960s, the university continued expansion plans by building the Evansdale Residential Complex to house approximately 1,800 students, the Mountainlair student union, and several engineering and the creative arts facility on the Evansdale campus. In 1970 the WVU Coliseum, a basketball facility with a capacity of 14,000, opened near the new campus.[27] As the facilities expanded, the university researched ways to move its growing student population across the split campuses and to solve its worsening traffic congestion. The resulting Personal Rapid Transit system opened in 1973 as the world's first automated rapid transit system.[32]

Post-expansion and 21st century

[edit]

The student population continued to grow in the late 1970s, reaching 22,000. With no room for growth on the downtown campus, the football stadium was closed, and the new Mountaineer Field was opened near the Medical campus on September 6, 1980. Mountaineer Field would later be named Mountaineer Field at Milan Puskar Stadium.[25] After an $8 million donation to the university, Ruby Memorial Hospital opened on the Medical campus in 1988, providing the state's first level-one trauma center. Early the next year, the undefeated Mountaineer football team, led by Major Harris, made it to the national championship game before losing to Notre Dame in the Fiesta Bowl.

During the 1990s the university developed several recreational activities for students, including FallFest and WVU "Up All Night". While the programs were created to provide safe entertainment for students and to combat WVU's inclusion as one of the nation's top party schools,[33] they also garnered national attention as solutions for reducing alcohol consumption and partying on college campuses across the country.[34][35] In 2001, a $34 million, 177,000-square-foot (16,400 m2) recreation facility opened on the Evansdale campus, providing students with exercise facilities, recreational activities, and personal training programs.[36]

WVU reached a new level of athletic success to start the new millennium. The football team featured a 3‑0 BCS bowl record, ten consecutive bowl game appearances, a #1 ranking in the USA Today Coaches' Poll, three consecutive 11‑win seasons amassing a 33–5 record, 41 consecutive weeks in the top 25, and 6 conference championships.[37][38] The men's basketball team won the 2007 NIT Championship and the 2010 Big East championship, while appearing four times in the sweet sixteen, twice in the elite-eight, and once in the final-four of the NCAA tournament.[39][40] The athletic successes brought the university a new level of national exposure, and enrollment has since increased to nearly 30,000 students.[41]

On April 24, 2008, the Pittsburgh Post-Gazette reported the university had improperly granted an MBA to Heather Bresch, the daughter of the state's governor Joe Manchin and an employee of Mylan, a pharmaceutical company whose then-chairman Milan Puskar was one of the university's largest donors.[42] In the aftermath, the university determined Bresch's degree had been awarded without the prerequisite requirements having been met. They subsequently rescinded it, leading to the resignation of the president Michael Garrison, provost Gerald Lang, and business school dean Steve Sears. Garrison had been profiled as a trend toward non-traditional university presidents by the Chronicle of Higher Education[43] and Inside Higher Ed,[44] but the Faculty Senate approved a vote of no confidence in the search that selected him.[45] C. Peter McGrath was named interim president in August 2008.[46] James P. Clements became WVU's 23rd president on June 30, 2009. He had previously served as provost at Towson University.[47] On September 16, 2009, Michele G. Wheatly was named Provost and Vice President for Academic Affairs.[48] In November 2013, James P. Clements was selected to be Clemson University's 15th president.[49] E. Gordon Gee served as interim president and continues to serve as the president; this was Dr. Gee's second time in this role, having first served as president of WVU in 1981.[50]

On August 11, 2023, facing financial difficulties, a proposal to cut 7% of the university's faculty and eliminate 32 major programs offered at its Morgantown campus was announced. These cuts will affect some humanities disciplines, including the entire Department of World Language, Literature and Linguistics,[51] as well as some non-humanities programs, such as in pharmacy and engineering.[52] Within the first week of fall classes, on August 21, 2023, hundreds of students staged a walkout and held rallies on Morgantown's Downtown and Evansdale campuses to show opposition to the proposal. Participants wore red in honor of the striking coal miners who fought in the Battle of Blair Mountain. The event was organized by the West Virginia United Students' Union,[53] which began organizing in response to potential reductions and discontinuations while the program reviews were still in process.[54] Shortly thereafter, the WVU Faculty Assembly approved a vote of "no confidence" in President Gordon Gee.[55]

Campus

[edit]

The Morgantown campus comprises three sub-campuses. The original main campus, typically called the Downtown Campus, is in the Monongahela River valley on the fringes of downtown Morgantown. This part of the campus includes eight academic buildings on the National Register of Historic Places. The Downtown Campus comprises several architectural styles predominantly featuring red brick including Victorian Second Empire, Federal, Neoclassical, and Collegiate Gothic among others. The Evansdale Campus, a mile and a half north-northwest, on a rise above the flood plain of the Monongahela River, was developed in the 1950s and 1960s to accommodate a growing student population since space for expansion was limited at the Downtown Campus. The Health Sciences Campus, in the same outlying area (but on the other side of a ridge), includes the Robert C. Byrd Health Sciences Center, the Erma Byrd Biomedical Research Facility, Ruby Memorial Hospital, Chestnut Ridge Hospital, Mary Babb Randolph Cancer Center, WVU Healthcare Physicians Office Center, Rockefeller Neuroscience Institute, WVU Eye Institute, and the WVU Children's Hospital.

The Health Sciences Campus is near Mountaineer Field, over a ridge from the Evansdale Campus.

Core Arboretum

[edit]The Core Arboretum is a 91-acre (37 ha) arboretum owned by West Virginia University and on Monongahela Boulevard in Morgantown, West Virginia. It is open to the public daily without charge.[57]

The Arboretum's history began in 1948 when the university acquired its site. Professor Earl Lemley Core (1902–1984), chairman of the Biology Department, then convinced President Irvin Stewart to set the property aside for the study of biology and botany. In 1975 the Arboretum was named in Core's honor.

The Arboretum is now managed by the WVU Department of Biology and consists of mostly old-growth forests on steep hillside and Monongahela River floodplain. It includes densely wooded areas with 3.5 miles (5.6 km) of walking trails, as well as 3 acres (12,000 m2) of lawn planted with specimen trees.

The Arboretum has a variety of natural habitats in which several hundred species of native WV trees, shrubs, and herbaceous plants may be found. Some of the large trees are likely over 200 years old.[citation needed]

Campus safety

[edit]The university created WVU Alert, a text-based alert system for quickly disseminating emergency situations to faculty, staff, and students.[58] WVU also uses LiveSafe, a smart phone application that enables users to anonymously report crimes or safety concerns, or to use the walk safe feature which allows the user to invite a friend to monitor their location while they walk.[59] Additionally, there are 37, easily accessible, blue-lit towers housing emergency phones across the WVU campuses that automatically dial 911 in the event of an emergency.[60]

The West Virginia University Police Department (UPD) is the largest campus police department in the state and the only campus law enforcement agency in the state accredited by the International Association of Campus Law Enforcement Administrators.[61] The UPD has a sworn officer operations division, a central communication unit, a student cadet unit, investigations, K-9 teams and other support services. Officers have the same authority and powers as city and county police officers.[59]

Transportation

[edit]

Due to the distance between WVU's three campuses, the university built the innovative Personal Rapid Transit (PRT) system to link the campuses (Downtown, Evansdale, and Health Sciences) and reduce student traffic on local highways. Boeing began construction on the Personal Rapid Transit (PRT) system in 1972. The unique aspect that makes the system "personal" is that a rider specifies their destination when entering the system and, depending on the system load, the PRT can dispatch a car that will travel directly to that station.

The PRT began operation in 1973, with U.S. President Richard Nixon's daughter, Tricia, aboard one of five prototype cars for a demonstration ride.[62] The PRT handles 16,000 riders per day (as of 2005[update]) and uses approximately 70 cars.

The system has 8.7 miles (14.0 km) of guideway track and five stations: Walnut, Beechurst, Engineering, Towers, and Medical/Health Sciences. The vehicles are rubber-tired, but the cars have constant contact with a separate electrified rail. Steam heating keeps the elevated guideway free of snow and ice. Although most students use the PRT, this technology has not been replicated at other sites for various reasons, including the high cost of maintaining the heated track system in winter.[63]

The PRT cars are painted in school colors (blue with gold trim) and feature the university name and logo on the front. Inside, the seats are light beige fiberglass and the carpeting is blue. Each car has eight seats with an overall capacity of 20 people, including standing room.

The National Society of Professional Engineers named the WVU PRT one of the top 10 engineering achievements of 1972,[62] and in 1997 The New Electric Railway Journal picked the WVU PRT as the best people mover in North America (for 1996).[64]

In 2006 the U.S. Department of Transportation and U.S. Environmental Protection Agency dubbed WVU one of the best workplaces for commuters.[65]

Each autumn, during Mountaineer Week celebrations, a special PRT car is placed in front of the Mountainlair student union where groups of students participate in the "PRT Cram" with the objective of squeezing in as many people as possible. A record of 97 was set in 2000.[66]

The PRT has become a cultural mainstay of the WVU campus. However, it is not without problems. One student was seriously injured in 2020 when a boulder collapsed onto the track, smashing a cart.[67] Two more students had to be transported to Ruby Memorial Hospital.[68]

Divisional campuses

[edit]WVU has two divisional campuses:

- Potomac State College of West Virginia University in Keyser

- West Virginia University Institute of Technology in Beckley

West Virginia University at Parkersburg, a primarily 2-year school, was a regional campus of WVU but has been independent since 2009.[69]

Academics

[edit]Reputation and rankings

[edit]| Academic rankings | |

|---|---|

| National | |

| Forbes[70] | 343 |

| U.S. News & World Report[71] | 216 (tie) |

| Washington Monthly[72] | 142 |

| WSJ/College Pulse[73] | 252 |

| Global | |

| QS[74] | 1,001–1,200 |

| THE[76] | Reporter[a] |

| U.S. News & World Report[77] | 606 (tie) |

WVU is classified among "R1: Doctoral Universities – Very high research activity".[78][79] According to the National Science Foundation, WVU spent $185.1 million on research and development in 2018, ranking it 121st in the nation.[80] WVU is affiliated with the Rockefeller Neurosciences Institute, dedicated to the study of Alzheimer's and other diseases that affect the brain.[81] WVU is also a leader in biometric technology research and the Federal Bureau of Investigation's lead academic partner in biometrics research.[82][83]

Admissions

[edit]Freshman West Virginia resident applicants must have a 2.0 GPA and either an SAT super score of 990 of 1600 or an ACT super score of 19 of 36. For non-residents the requirements are a GPA of 2.5 and either a super score SAT 1060 or a super score ACT of 21. College and program admission requirements for first-time freshmen vary by program.[84] The general freshman acceptance rate at WVU is 71.9% of applications received with an average entering student GPA of 3.42, an SAT super score of 1115 of 1600, and an ACT super score of 24 of 36.[85]

In the fall of 2020, the university relaxed its test score requirements for students applying for admission in response to the coronavirus pandemic. According to WVU assistant vice president of Enrollment Management George Zimmerman, if students are unable to take the SAT or ACT, they will still be admitted to WVU as long as they have shown academic ability in other areas of their application. The policy is said to be in effect until spring 2023.[86]

Curriculum

[edit]

West Virginia University is organized into 15 degree-granting colleges or schools and also offers an Honors College.

- College of Creative Arts and Media

- Davis College of Agriculture, Natural Resources & Design

- Eberly College of Arts & Sciences

- John Chambers College of Business & Economics

- Benjamin M. Statler College of Engineering & Mineral Resources

- College of Education & Human Services

- College of Law

- School of Dentistry

- School of Medicine

- School of Nursing

- School of Pharmacy

- School of Public Health

- College of Physical Activity & Sport Sciences

- University College

- Honors College

WVU's forensics and investigative science program was originally created through a partnership with the Federal Bureau of Investigation. The program is accredited by the American Academy of Forensic Sciences and is the official library holdings repository for the International Association for Identification. The program includes three main areas of emphasis, the examiner track, which specializes in crime scene investigation and comparison sciences, the biology track, which specializes in body fluids and DNA analysis, and the chemistry track, which specializes in the chemical identification of seized drugs, fire debris, trace evidence and explosives. Facilities include four "crime-scene" houses, a vehicle processing garage, a ballistics laboratory, and numerous traditional laboratories and classrooms in Ming Hsieh Hall and Oglebay Hall. A separate Criminology & Investigative Sciences major was later added to the Eberly College of Arts and Sciences. The College of Business and Economics also provides a certificate in forensic accounting and fraud examination.

WVU robotics teams have won several international competitions such as the NASA Robotic Mining Competition and the NASA/NIA RASC-AL Exploration Robot-OPS Challenge. In 2016, a WVU team[87] led by Dr. Yu Gu won the final NASA Sample Return Robot Centennial Challenge with a $750,000 prize.[88]

Biometrics is an engineering-centric field of study offered at WVU, the first institution in the world to establish a Bachelor of Science degree in Biometric Systems. In 2003 the university also founded the initial chapter of the Student Society for the Advancement of Biometrics (SSAB).[89] The program, in the Lane Department of Computer Science and Electrical Engineering (LCSEE), provides a firm understanding of the underlying electrical engineering and computer engineering disciplines that support biometric applications. On February 6, 2008, WVU became the national academic leader for the FBI's biometric research.[90] WVU is also the founding site for the Center for Identification Technology Research (CITeR), focusing on biometrics and identification technology. CITeR maintains and develops collaborative relationships with other academic institutions to meet research needs.[91]

The Robert C. Byrd Health Sciences Center is on West Virginia University's Evansdale Campus and houses the Schools of Dentistry, Medicine, Nursing, and Pharmacy. These schools grant doctoral and professional degrees in 16 different fields, as well as a variety of other Master's and Bachelor's degrees.[92] For 2012 U.S. News & World Report ranked WVU's Medical School ninth in the United States for rural medicine.[93]

Also on the Health Sciences Campus is WVU's local teaching hospital, Ruby Memorial Hospital, which is one of only two designated Trauma I hospitals in the state.

Libraries

[edit]

The West Virginia University Libraries encompasses seven libraries and the WVU Press, including the Downtown Campus Library, Evansdale Library, Health Sciences Library (Morgantown), Law Library, Health Sciences Library (Charleston), the Mary F. Shipper Library at Potomac State College in Keyser, the Beckley Library at the WVU Institute of Technology, and the West Virginia and Regional History Center (the world's largest collection of West Virginia-related research material), is in the Wise Library on the Downtown Campus.[94] Collections include the Appalachian Collection, Digital Collections, Government Documents, Map Collection, Myers Collection, Patent and Trademarks, Rare Books Collections, and Theses and Dissertations. West Virginia University libraries contain nearly 1.5 million printed volumes, 2.3 million microforms, more than 10,000 electronic journals, and computers with high-speed Internet access.

The Evansdale Library supports the academic programs and research centered on the Evansdale Campus. The library holds materials in the disciplines of agriculture, art, computer science, education, engineering, forestry, landscape architecture, mineral resources, music, physical education, and theater.[95] In addition to the collections, Evansdale Library is home to da Vinci's Cafe,[96] an Information Technology Services Big Prints! poster printing lab,[97] and the Academic Innovation Teaching and Learning Commons Sandbox.[98]

The university co-publishes the Labor Studies Journal with the United Association for Labor Education.

Student life

[edit]| Race and ethnicity[99] | Total | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| White | 82% | ||

| Other[b] | 5% | ||

| Hispanic | 4% | ||

| Foreign national | 4% | ||

| Black | 4% | ||

| Asian | 2% | ||

| Economic diversity | |||

| Low-income[c] | 26% | ||

| Affluent[d] | 74% | ||

Events

[edit]FallFest welcomes students to the university by providing an evening of entertainment and musical performances traditionally held during the first week of the fall semester and traditionally at the Mountainlair Student Union.[100] The event began in 1995 as a safe alternative to partying and has become one of the largest University-sponsored events, typically drawing crowds of 15,000 or more.[101] The celebration has been highlighted by a series of evening concerts by renowned artists. A dance party, film festival, comedy show, and several indoor musical performances are also featured.

Mountaineer Week is a celebration of WVU tradition and Appalachian heritage that began in 1947.[102] Festivities have expanded to include competitions among WVU students, designed to honor school and state pride. A beard-growing competition introduced in 1949 has continued throughout the event's history. Participants must shave before the panel of judges that also chooses the winner at the end of the competition.[103] The Mr. and Ms. Mountaineer competition has been included in Mountaineer Week since 1962, honoring one male and one female student who show "outstanding school spirit, academic excellence, and extracurricular involvement". The annual PRT Cram features the unique PRT system, where students compete to fit the maximum number of riders on a special-model PRT car with the windows removed. The record was set in 2000 when 97 students fit inside one PRT car.[102]

The Lighting of Woodburn Hall is an annual university ceremony held in early December to light historic Woodburn Hall for the holiday season. The event began in 1987 and is open to the public. Christmas carols are typically sung and donations are taken at the event to support community organizations. Patients from WVU's Children's hospital are often selected to light the Hall.[104]

Fall Family Weekend is an opportunity for students' family members to experience WVU campus life by attending classes, athletic events, college presentations, and student events such as WVU "Up All Night". Tours of the campus facilities are offered by individual colleges and organizations, including tours of the PRT.[105]

Homecoming weekend activities include the Alumni Band-led homecoming parade through downtown Morgantown, the crowning of the royalty, and a football game with a performance by the WVU Alumni band. Student organizations participate in the parade by designing floats. Receptions are held by colleges, student groups, and the alumni center.[106]

Greek Week is held during the spring semester, providing a venue for competition between Greek organizations. Highlights include airband events, where organizations compete in cheerleading and dance routines, and sports competitions on the Mountainlair recreational field. The competitions strive to highlight WVU's student spirit and present a positive image of the fraternities and sororities.[107]

Recreation

[edit]

The Mountainlair Student Union, commonly called "the Lair" by students, is the three-floor student union building at WVU. The building dates to 1968 and replaced an earlier structure built in 1948.[108] The student union offers many recreational opportunities to students including a movie theater, bowling alley, pool hall, ballrooms, video game arcade, a cafeteria-style restaurant, and a collection of fast food restaurants.[109]

The Student Recreation Center is a 177,000-square-foot (16,400 m2) recreation facility that opened before the 2001 academic year with an initial construction cost of $34 million.[36] The facility offers a six-lane swimming pool, 20‑seat spa, 17,000 square feet (1,600 m2) of cardio and free-weight equipment, an elevated running track, basketball courts, volleyball and badminton courts, glass squash and racquetball courts, and a 50-foot (15 m) climbing wall.[110] The center also offers a variety of wellness programs, personal training, child care services, exercise classes, and intramural activities.

The Mountaineer Adventure Program (MAP) offers several activities including Adventure WV, Challenge Course, and International Trips. Adventure WV is focused on providing guidance to freshmen and sophomores through various outdoor orientation expeditions. The Challenge Course program uses a recreational facility designed to teach teamwork and problem-solving skills through physical interaction. International Trips offers worldwide recreational opportunities to places like Fiji and Peru, as well as study abroad credit courses.[111] Several of the MAP programs provide University-accepted credit hours.

The Outdoor Recreation Center, a division of the Student Recreation Center, helps students find recreational activities locally and in other parts of West Virginia. The center sponsors some trips, including whitewater rafting on the Cheat River and hiking in the Monongahela National Forest.[110] Students can take advantage of West Virginia's natural wilderness by renting outdoor recreational equipment for hiking, camping, climbing, fishing, biking, skiing, and whitewater rafting, all of which is available with minimal travel time. WVU's main campus is next to the Monongahela River along which runs the Caperton Trail, also known as the "Rail Trail", a 10-mile (16 km) paved path for walking, running, or biking.[112] Other connecting trails total 43 miles (69 km) in additional length, extending from the Pennsylvania border to Prickett's Fort State Park. Many student groups take day trips to the nearby Coopers Rock State Forest, which is less than 15 miles (24 km) from WVU's campus.[113]

Student organizations

[edit]West Virginia University offers more than 400 student-run organizations and clubs. Many of the organizations are associated with academia, religion, culture, military service, politics, recreation, or sports.[114] New student groups may be formed by submitting a constitution and petition to become recognized as a student organization.

Student Government Association

[edit]The Student Government Association (SGA) serves as representatives for the student body and as a liaison to the university administration and officials. The President of the Student Body also serves as a full voting member of the university's Board of Governors.

Fraternities and sororities

[edit]

WVU Greek fraternities are Phi Beta Sigma, Alpha Epsilon Pi, Alpha Gamma Rho, Kappa Alpha Order, Lambda Chi Alpha, Phi Delta Theta, Phi Kappa Psi, Pi Kappa Phi, Sigma Alpha Epsilon, Sigma Nu, Phi Sigma Phi, Sigma Phi Delta, Sigma Phi Epsilon and Theta Chi. Greek sororities are Zeta Phi Beta, Alpha Omicron Pi, Alpha Phi, Alpha Xi Delta, Chi Omega, Delta Gamma, Kappa Kappa Gamma, Pi Beta Phi, and Sigma Kappa.[115]

Fraternity controversies

In 2014, 18-year-old Kappa Sigma pledge Nolan Burch died during a hazing incident at the fraternity house. Police say his blood-alcohol level was 0.493% at the time of his death.[116] A lawsuit was settled over the student's death in 2018 for $250,000.[117]

In 2019, City Drive Studios produced the documentary "Breathe, Nolan, Breathe", which details what led up to Nolan's death. The film begins with security footage inside the Kappa Sigma house, showing a fraternity brother performing CPR on Nolan's limp body hours after he was dragged inside. The brother kept repeating the words, "breathe, Nolan, breathe." Video also shows fraternity brothers taking videos of Burch lying on a wooden plank, walking around him, and even kicking him.[118] The film is being used by the university to kick off a bystander awareness campaign.[119] According to City Drive Studios, " The purpose of this film is to stop this from ever happening again and to save lives."[120]

In 2018 several WVU fraternities chose to disassociate themselves after the school sent out stricter rules and regulations for Greek life. For example, Sigma Chi was restricted to one social event per semester. David Coram of Sigma Chi says this was one of the main reasons the fraternity decided to disassociate. WVU also decided to raise the required GPA for rushing students from 2.5 to 2.75. For Farris, the biggest concern with the breakaway is student safety, reports the WV Gazette-Mail. He explained how the university would not be able to help in situations such as an injury or sexual assault if they were not recognized by the school.[121]

2018 brought another fraternity incident as, according to WVU, senior finance major David Rusko, 22, fell down steps and was knocked unconscious at the fraternity house where he was visiting after a football game. An investigation found two hours elapsed between the fall and when medical help was sought. West Virginia University announced that three students were no longer enrolled at the university and 15 others agreed to other disciplinary action as a result.[122][123]

Student media

[edit]The Daily Athenaeum, nicknamed the DA, is the 9th-largest newspaper in West Virginia.[124] Offered free on campus, it generates income through advertisements and student fees. The paper began in 1887 as a weekly literary magazine, with writing, editing and production taken over by the newly formed School of Journalism in the 1920s. In 1970, the paper split from the School of Journalism and became an independent campus entity governed by the Student Publications Board. The DA was voted as the Princeton Review's 10th-best college newspaper in the United States in 2005, 15th in 2006, and 8th in 2007.[125]

WWVU-FM, called U92 or The Moose, plays new music, talk shows, and newscasts. On the air since 1982, U92 can be heard in the Morgantown area at 91.7 FM and also streams live on the internet. In 2007 the station was one of four college radio stations nominated for College Music Journal's Station of the Year Award.[126] In 2015 CMJ awarded the station with three awards including Station of the Year.[127]

The Mountaineer Jeffersonian was a news, economic, and political journal founded by WVU students. The publication was founded in 2008 and ceased publication in 2011.

Student health

[edit]The Student Center of Health, also known under the label "WELLWVU", provides services related to student health, disease prevention, and awareness. The Carruth Center for Psychological and Psychiatric Services offers therapy to any WVU student.[128] The Robert C. Byrd Health Science Center and the associated West Virginia University Hospitals, on the Health Science Campus, serve as West Virginia's largest healthcare institution.[129] The hospitals provide a comprehensive set of healthcare needs for local and regional patients. WVU students have full access to healthcare resources, which are accessible from the PRT towers station.

WVU Student Health Services

[edit]Starting with the Fall 2014 semester WVU implemented a mandatory student health insurance policy, with an opt-out. All domestic students at West Virginia University and WVU Tech, enrolled in 6 or more credit hours and international students enrolled in 1 or more credit hours will be required to carry health insurance coverage.[130]

With the opening of the new Student Health and Wellness building on the Evansdale Campus, WVU Medical Corporation now operates the medical services of Student Health. This is a WVU Urgent Care Clinic office and is the primary care provider to students who use WVU's Aetna Health Insurance policy. The Clinic is open 7 days a week.[131]

Mental Health Record

[edit]As of the end of the Spring 2020 semester, two students died by suicide after not being able to seek counseling at the Carruth Center for Mental Health. There have also been numerous accounts of a culture of alcoholism[132] and mental illness. The school has offered limited support via email regarding the deaths of these students.

Arts and entertainment

[edit]WVU Arts & Entertainment (A&E) sponsors entertainment events for students throughout the academic year. The department organizes the annual FallFest event, which features popular musicians, comedians, and other performers. WVU A&E annually hosts several concerts at the WVU Coliseum and Canady Creative Arts Center, with past performances by Akon, The All-American Rejects, The Fray, Kelly Clarkson, Ludacris, Maroon 5, Reba McEntire, Willie Nelson, and 50 Cent among others.[101] The Canady Creative Arts Center was constructed in 1967, it included a new Möller pipe organ.[133]

The West Virginia Public Theater (WVPT) is one of two professional musical theaters in West Virginia. The group is near WVU's campus and performs several Broadway numbers yearly.[134]

The 5,300-square-foot (490 m2) Art Museum of West Virginia University features touring exhibitions and displays a collection including over 2,500 works of art from the Appalachian region, Asia, and Africa.[135]

The Royce J. and Caroline B. Watts Museum, on the Evansdale campus, features tools, equipment, artifacts, photos, and other items related to West Virginia's coal and petroleum industries.

Athletics

[edit]

The school's sports teams are called the Mountaineers and compete in the NCAA's Division I. The school has teams in 17 college sports and has won several national championships, including 19 NCAA Rifle Championships as of 2018[update]. Formerly a full member of the Big East Conference in all sports, on October 28, 2011, the school accepted an invitation to join the Big 12 Conference and became a member on July 1, 2012.

Notable athletes from West Virginia University include Ashley Lawrence, Jerry West, Jim Braxton, Marc Bulger, Avon Cobourne, Mike Compton, Noel Devine, Cecil Doggette, D'or Fischer, Mike Gansey, Marc "Major" O. Harris, Chris Henry, Joe Herber, Jeff Hostetler, Chuck Howley, Sam Huff, Darryl Talley, "Hot Rod" Hundley, Adam "Pacman" Jones, Joe Stydahar, Dan Mozes, Kevin Pittsnogle, Jerry Porter, Todd Sauerbrun, Steve Slaton, Ray Gaddis, Rod Thorn, Oliver Luck, Mike Vanderjagt, Pat White, Quincy Wilson, Amos Zereoué, Greg Jones, Joe Alexander, Owen Schmitt, Georgann Wells, Geno Smith, Ginny Thrasher, Pat McAfee, Tavon Austin, Miles McBride, and Jedd Gyorko.

Football

[edit]WVU has had two undefeated regular seasons; they went 11–0 in 1988 and 1993. However, West Virginia lost both bowl games, 34‑21 to Notre Dame in the National Championship, and 41–7 to Florida. The 2005 season and the 2006 season produced the first consecutive 11-win seasons in school history.[136] In the 2007 season, the Mountaineers started the season as the #3-ranked team, the highest preseason ranking in school history. That team eventually was ranked #1 in the Coaches Poll and finished the season with a third consecutive 11-win season after their Fiesta Bowl victory.

Basketball

[edit]West Virginia men's basketball has competed in three basketball championship final matches: the 1959 NCAA final, the 1942 NIT final (at that time, the NIT was considered more prestigious than the NCAA), and the 2007 NIT Championship. They lost to California in the 1959 NCAA finals, while the Mountaineers won the 1942 NIT Championship over Western Kentucky, and the 2007 NIT contest over Clemson. In 1949 future Mountaineers head coach, Fred Schaus, became the first player in NCAA history to record 1,000 points.

Recently, West Virginia reached the Final Four of the 2010 NCAA Men's Division I Basketball Tournament, led by West Virginia coach and former WVU player Bob Huggins. The Mountaineers won the 2010 Big East men's basketball tournament and received a #2 seed in the East Region of the 2010 NCAA Division I men's basketball tournament.

In 2015, West Virginia reached the Sweet Sixteen of the 2015 NCAA Division I men's basketball tournament. They were eliminated from the tournament after losing to Kentucky. In 2018, West Virginia again reached the Sweet Sixteen of the 2018 NCAA Division I men's basketball tournament. They were eliminated from the tournament after losing in the fourth round to #1 seed and eventual champion Villanova.[137]

Soccer

[edit]Since joining the Big 12 Conference ahead of the 2012 season, West Virginia women's soccer has posted a 27–1–3 record in regular-season league games. In 2016, the Mountaineers claimed their fifth consecutive outright regular-season league championship, becoming the first team in Big 12 history to accomplish that feat. West Virginia also won back-to-back Big 12 tournament championships in 2013 and 2014, as well as two additional Big 12 tournament championships in 2016 and 2018. The Mountaineers are coached by Nikki Izzo-Brown, the program's only head coach.

West Virginia men's soccer competes in the Sun Belt Conference.

Rifle

[edit]With a total of 26 individual NCAA National Champions and 19 team NCAA National Championship titles, West Virginia University's rifle team is the most successful rifle program in the history of the NCAA. Their most recent National Championship as a team was won in 2017. The Mountaineers compete in the Great America Rifle Conference where they have won 11 regular-season conference championships. The team's home matches take place at the WVU Rifle Range which opened in 2010. Virginia Thrasher, who won a gold medal in the women's 10-meter air rifle at the 2016 Summer Olympics, was on the Mountaineers rifle team from 2015 to 2019.[138]

Marching band

[edit]The West Virginia University Mountaineer Marching Band is nicknamed "The Pride of West Virginia." The 340-member band performs at every home football game and makes several local and national appearances throughout the year.

Fanbase

[edit]

In a state that lacks professional sports franchises, West Virginians passionately support West Virginia University and its athletics teams.[139] Men's basketball head coach Bob Huggins, a former Mountaineer basketball player who was born in Morgantown, stated that the "strong bond between the university and the people of West Virginia" is a relationship that is difficult for non-natives to understand.[140]

Some WVU fans, primarily in the student sections, better known as the "Mountaineer Maniacs" have developed a reputation for unruly behavior, being compared to "soccer hooligans" by GQ magazine.[141][142] At some events, there have been cases of objects thrown onto the field or at opposing teams.[143][144] There were also issues with small-scale fires, most notably of couches, being set after games; over 1,100 intentionally ignited street fires were reported from 1997 to 2003.[141]

Members of the Morgantown-area community volunteered as Goodwill City Ambassadors for the first time in the fall of 2012 to welcome visiting fans to the football games. The Goodwill City initiative is a collaborative effort of the City of Morgantown, WVU, Morgantown's Dominion Post, and community residents.

Pageantry

[edit]

The Mountaineer was adopted in 1890 as the official school mascot and unofficially began appearing at sporting events in 1936.[145] A new Mountaineer is selected each year during the final two men's home basketball games, with the formal title "The Mountaineer of West Virginia University". The new Mountaineer receives a scholarship, a tailor-made buckskin suit with a coonskin hat, and a period rifle and powder horn for discharging when appropriate and safe. The mascot travels with most sports teams throughout the academic year. While not required, male mascots traditionally grow a beard.

The "Flying WV" is the most widely used logo in West Virginia athletics. It debuted in 1980 as a part of a football uniform redesign by Coach Don Nehlen, and was adopted as the official logo for the university in 1983.[146] While the "Flying WV" represents all university entities, unique logos are occasionally used for individual departments. Some examples include the script West Virginia logo for the WVU Department of Intercollegiate Athletics and the interlocking WV logo used in baseball.[147]

Fight songs of West Virginia University include "Hail, West Virginia" and "Fight Mountaineers". The West Virginia University Alma Mater was composed in 1937, and is sung before every home football game. The crowd sings along as the WVU Marching Band stands playing it on the field, as part of the pregame show.

"Old gold and blue", the official University colors, were selected by the upperclassmen of 1890 from the West Virginia state seal.[145] While the official school colors are old gold and blue, brighter gold is used in official university logos and merchandise. This change in color scheme is often cited for the lack of a universal standard for colors during the 19th century when the university's colors were selected. Additionally, the brighter gold is argued to create a more intimidating environment for sporting events. The university accepts "gold and blue" for the color scheme, but states clearly that the colors are not "blue and gold", to distinguish West Virginia from its rival, the University of Pittsburgh.

Sporting traditions

[edit]

The unofficial song of the university, "Take Me Home, Country Roads" by John Denver, became an official West Virginia state song on March 8, 2014.[148] In 1980 John Denver performed his hit song "Take Me Home, Country Roads" at the dedication of Mountaineer Field, and it has since become a tradition for fans to remain in the stands following every Mountaineer victory and sing the song with the players. Although the tradition originated during football games, it is now recognized throughout the university, with the song performed at various athletic events and ceremonies. Sports Illustrated named the singing of "Country Roads" as one of the must-see college traditions.[149]

The Pride of West Virginia is the official marching band of the university. The band's football pre-game show includes traditions such as the Drumline's "Tunnel" and "Boogie" cadences, the 220‑beat per minute run-on cadence to start the performance, marching the "WV" logo down the field to the university fight song, "Fight Mountaineers", expanding circles during Simple Gifts, and the formation of the state's outline during "Hail, West Virginia".

The Firing of the Rifle is a tradition carried out by the Mountaineer Mascot to open several athletic events. The Mountaineer points the gun into the air with one arm and fires a blank shot from a custom rifle, a signal to the crowd to begin cheering at home football and basketball games. The Mountaineer also fires the rifle every time the team scores during football games.

The Carpet Roll is a WVU Men's Basketball tradition. In 1955 Fred Schaus and Alex Mumford devised the idea of rolling out an elaborate gold and blue carpet for Mountaineer basketball players to use when taking the court for pre-game warm-ups. In addition, Mountaineer players warmed up with a special gold and blue basketball. The university continued this tradition until the late 1960s when it died out, but former Mountaineer player Gale Catlett reintroduced the carpet when he returned to West Virginia University in 1978 as head coach of the men's basketball team.

Popular culture

[edit]- West Virginia University is a location in the game Fallout 76, as Vault-Tec University[150]

Notable people

[edit]Notable alumni

[edit]Notes

[edit]- ^ Institution submitted data but didn't meet the criteria to be ranked.[75]

- ^ Other consists of Multiracial Americans & those who prefer to not say.

- ^ The percentage of students who received an income-based federal Pell grant intended for low-income students.

- ^ The percentage of students who are a part of the American middle class at the bare minimum.

References

[edit]- ^ "Timeline – WVU 150th Anniversary". West Virginia University. Archived from the original on May 23, 2019. Retrieved May 23, 2019.

- ^ As of June 30, 2023. "U.S. and Canadian 2023 NCSE Participating Institutions Listed by Fiscal Year 2023 Endowment Market Value, Change in Market Value from FY22 to FY23, and FY23 Endowment Market Values Per Full-time Equivalent Student" (XLS). National Association of College and University Business Officers (NACUBO). February 15, 2024. Retrieved May 15, 2024.

- ^ "WVU Board begins process to extend President Gee's contract". WVU Today. West Virginia University. April 12, 2019. Retrieved May 23, 2019.

- ^ "Maryanne Reed named provost at West Virginia University". WVU Today. West Virginia University. August 12, 2024. Retrieved October 18, 2019.

- ^ a b c d "FAQ: How many students are enrolled?". West Virginia University. Retrieved August 12, 2024.

- ^ "West Virginia University Facts".

- ^ "WVU Brand Center". Retrieved June 7, 2016.

- ^ a b "About WVU". West Virginia University. Retrieved May 23, 2019.

- ^ Doherty, William T.; Festus P. Summers (1982). West Virginia University: Symbol of Unity in a Sectionalized State. West Virginia University Press. p. 8. ISBN 0-937058-16-5.

- ^ a b "West Virginia College". Morgantown Weekly Post. August 10, 1867. Retrieved August 16, 2010.

- ^ Doherty, William T.; Festus P. Summers (1982). West Virginia University: Symbol of Unity in a Sectionalized State. West Virginia University Press. p. 11. ISBN 0-937058-16-5.

- ^ "About Monongalia County". WVU Extension Services. Archived from the original on February 2, 2011. Retrieved August 17, 2010.

- ^ "A Brief History of Marin Hall". West Virginia University. Archived from the original on August 31, 2010. Retrieved August 17, 2010.

- ^ "WVU College of Law History". WVU College of Law. Archived from the original on August 20, 2010. Retrieved August 18, 2010.

- ^ "Woodburn Hall, WVU's Historic Centerpiece". West Virginia University. Archived from the original on July 19, 2011. Retrieved August 17, 2010.

- ^ "National Register Information System". National Register of Historic Places. National Park Service. July 9, 2010.

- ^ George A. Smyth; Ted McGee & James E. Harding (February 1974). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: Woodburn Circle" (PDF). State of West Virginia, West Virginia Division of Culture and History, Historic Preservation. Retrieved August 18, 2011.

- ^ Lee R. Maddex (January 1991). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: Vance Farmhouse" (PDF). State of West Virginia, West Virginia Division of Culture and History, Historic Preservation. Retrieved August 18, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f "West Virginia University: 1867–2003". West Virginia University. Archived from the original on November 27, 2007. Retrieved August 17, 2010.

- ^ WVU Student Government (2007). "8". Dream Big, Dream Here. Tapestry Press. ISBN 978-1-59830-150-2.

- ^ a b "Portrait of Eva Hubbard". West Virginia and Regional History Center On-View. Retrieved March 30, 2023.

- ^ "A History of the Integration of Sports at WVU". West Virginia University. Archived from the original on August 31, 2010. Retrieved August 17, 2010.

- ^ Rodney S. Collins (March 1980). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: Stewart Hall" (PDF). State of West Virginia, West Virginia Division of Culture and History, Historic Preservation. Retrieved August 18, 2011.

- ^ Randall Gooden (July 1985). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: Purinton House" (PDF). State of West Virginia, West Virginia Division of Culture and History, Historic Preservation. Retrieved August 18, 2011.

- ^ a b c "WVU Year-by-Year". West Virginia University. Archived from the original on June 27, 2010. Retrieved August 19, 2010.

- ^ Randall Gooden (July 1985). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: Stalnaker Hall" (PDF). State of West Virginia, West Virginia Division of Culture and History, Historic Preservation. Retrieved August 18, 2011.

- ^ a b Bill Bradley (2009). ESPN College Basketball Encyclopedia: The Complete History of the Men's Game. ESPN. p. 36. ISBN 978-0-345-51392-2.

- ^ Randall Gooden (July 1985). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: Elizabeth Moore Hall" (PDF). State of West Virginia, West Virginia Division of Culture and History, Historic Preservation. Retrieved August 18, 2011.

- ^ Stanley Bumgardner & Barbara J. Howe (January 1989). "National Register of Historic Places Inventory Nomination Form: Men's Hall" (PDF). State of West Virginia, West Virginia Division of Culture and History, Historic Preservation. Retrieved August 18, 2011.

- ^ "The Mountaineer". MSN Sports. Archived from the original on July 14, 2011. Retrieved August 19, 2010.

- ^ "NBA Encyclopedia Playoff Edition". ESPN. Retrieved August 20, 2010.

- ^ "Still in a Class of Its Own". Progressive Engineer. Archived from the original on July 19, 2011. Retrieved August 20, 2010.

- ^ "List of Party Schools By Princeton Review". Associated Press. Retrieved August 13, 2010.[dead link]

- ^ "WVU officials say program worth the cost". Charleston Daily Mail. Retrieved August 12, 2010.

- ^ Party Response Archived September 28, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b "Amazing New Rec Center". Charleston Gazette. Archived from the original on July 10, 2011. Retrieved August 13, 2010.

- ^ "A Championship Program". MSN Sports Net. Archived from the original on February 16, 2009. Retrieved August 20, 2010.

- ^ "2007 NCAA Football Rankings – Week 14 (November 25)". ESPN/AP. Retrieved August 20, 2010.

- ^ "2007 NIT Champions". NIT. Archived from the original on March 3, 2012. Retrieved August 20, 2010.

- ^ "Tradition of Champions". MSN Sports Net. Archived from the original on March 22, 2009. Retrieved August 20, 2010.

- ^ "WVU set record fall enrollment". West Virginia University. Retrieved August 20, 2010.

- ^ Ian Urbina, "University Investigates Whether Governor's Daughter Earned Degree", New York Times, January 22, 2008

- ^ Fain, Paul (February 15, 2008). "The Lobbyist as President". Chronicle of Higher Education. Retrieved September 20, 2012.

- ^ Redden, Elizabeth (March 14, 2008). "The Nontraditional President". Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved September 20, 2012.

- ^ Daily Athenaeum (May 23, 2007): "Faculty Senate votes 'no confidence'", by Tricia Fulks Archived November 11, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "WVU Admin". Archived from the original on December 15, 2013. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- ^ "WVU's 23rd president officially takes reins". Archived from the original on March 24, 2012.

- ^ "Wheatly named Provost at WVU". WVUToday. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- ^ "James P. Clements named president of Clemson University". WVUToday. Retrieved November 27, 2014.

- ^ "Welcome back, Gee: WVU community greets returning president with open arms". WVUToday. Retrieved November 27, 2014.

- ^ Richard Utz, "Beating the bottom line: Is language instruction doomed to fail at rural universities?" University Business, July 1, 2024.

- ^ Quinn, Ryan (August 11, 2023). "West Virginia U Plans to Cut 7% of Faculty, All Languages". Inside Higher Ed. Retrieved August 12, 2023.

- ^ "West Virginia University students push back on program and faculty cuts after $45M budget shortfall". AP News. August 21, 2023. Retrieved August 30, 2023.

- ^ Post, Erin Cleavenger, The Dominion (August 21, 2023). "Students' demands made clear during walk-out". Dominion Post. Retrieved August 30, 2023.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Nietzel, Michael T. (September 7, 2023). "West Virginia University Faculty Vote No Confidence In President Gee". Forbes. Retrieved August 30, 2023.

- ^ "Stalnaker Hall". West Virginia University. Archived from the original on February 19, 2009. Retrieved February 6, 2009.

- ^ "Home | Core Arboretum | West Virginia University". arboretum.wvu.edu.

- ^ "WVU Emergency Information". West Virginia University. Retrieved August 12, 2010.

- ^ a b "A letter from UPD Chief Roberts". The Daily Athenaeum - thedaonline. August 18, 2016.

- ^ "WVU Police". West Virginia University. Archived from the original on June 22, 2010. Retrieved August 12, 2010.

- ^ "WVU Police department awarded International Association of Campus Law Enforcement Administrators Accreditation". WVUToday. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- ^ a b "WVU News and Information Services (July 13, 2004 press release): "WVU PRT Station to Bear Name of People-Mover's Creator"". WVUToday. Archived from the original on November 11, 2007. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- ^ "Some Lessons from the History of Personal Rapid Transit (PRT)". University of Washington. Retrieved August 25, 2010.

- ^ "Rating the Rails" (annual performance-ratings feature by transit mode), The New Electric Railway Journal, Spring 1997, p. 30.

- ^ "WVU Named One of 'Best Workplaces' for Commuters by EPA, DOT Archived June 30, 2007, at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Wolfe, Billy (November 1, 2005). "PRT Cram". The Daily Athenaeum. Archived from the original on November 11, 2007. Retrieved November 6, 2007.

- ^ "Student injured in PRT-boulder collision speaks out". February 16, 2020.

- ^ "Three transported to hospital after boulder strikes car, PRT". February 10, 2020.

- ^ "FAQs about WVU Relationship". West Virginia University at Parkersburg. Archived from the original on April 10, 2015. Retrieved April 2, 2017.

- ^ "America's Top Colleges 2024". Forbes. September 6, 2024. Retrieved September 10, 2024.

- ^ "2023-2024 Best National Universities Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. September 18, 2023. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

- ^ "2024 National University Rankings". Washington Monthly. August 25, 2024. Retrieved August 29, 2024.

- ^ "2025 Best Colleges in the U.S." The Wall Street Journal/College Pulse. September 4, 2024. Retrieved September 6, 2024.

- ^ "QS World University Rankings 2025". Quacquarelli Symonds. June 4, 2024. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

- ^ Watkins, David (September 2, 2021). "Why we are including 'reporter' institutions in our World University Rankings". Times Higher Education. Retrieved February 5, 2024.

- ^ "World University Rankings 2024". Times Higher Education. September 27, 2023. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

- ^ "2024-2025 Best Global Universities Rankings". U.S. News & World Report. June 24, 2024. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

- ^ "Carnegie Classifications Institution Lookup". carnegieclassifications.iu.edu. Center for Postsecondary Education. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- ^ "About WVU". West Virginia University. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- ^ "Table 20. Higher education R&D expenditures, ranked by FY 2018 R&D expenditures: FYs 2009–18". ncsesdata.nsf.gov. National Science Foundation. Retrieved July 21, 2020.

- ^ Blanchette Rockefeller Neurosciences Institute (June 7, 2015). "Blanchette Rockefeller Neurosciences Institute – Home".

- ^ "Wall Street Journal Employer Rankings By Major". Wall Street Journal. September 14, 2010. Retrieved September 17, 2010.

- ^ "Wall Street Journal Employer Rankings: The Next Twenty". Wall Street Journal. September 13, 2010. Retrieved September 17, 2010.

- ^ "Admission Requirements". admissionswvu.edu. West Virginia University. Retrieved September 5, 2019.

- ^ "WVU Requirements for Admission". prepscholar.com. PrepScholar. Retrieved September 5, 2019.

- ^ "West Virginia University extends policy on admission tests". San Francisco Chronicle. April 26, 2021. Archived from the original on April 28, 2021. Retrieved April 28, 2021.

- ^ "NASA_Challenge". www2.statler.wvu.edu. Archived from the original on July 2, 2016. Retrieved September 29, 2016.

- ^ Hall, Loura (September 8, 2016). "NASA Awards $750K in Sample Return Robot Challenge". Retrieved September 29, 2016.

- ^ "SSAB WVU Chapter". Archived from the original on December 8, 2013. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- ^ "FBI Press". FBI. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- ^ "CITeR". Archived from the original on October 17, 2014. Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- ^ "Majors Listed by College & School". West Virginia University. Retrieved November 24, 2008.

- ^ "usnews.com: Medical Specialty Rankings: Rural medicine". Archived from the original on December 18, 2008.

- ^ "About the WVU Libraries". West Virginia University Libraries. Retrieved November 10, 2019.

- ^ "Evansdale Library". West Virginia University Libraries. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- ^ "West Virginia University Dining Services". Da Vinci's. West Virginia University Dining Services. Archived from the original on January 27, 2016. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- ^ "Big Prints!". West Virginia University Information Technology Services. Archived from the original on January 27, 2016. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- ^ "Sandbox". West Virginia University Teaching and Learning Commons. Retrieved January 13, 2016.

- ^ "College Scorecard: West Virginia University". United States Department of Education. Retrieved May 8, 2022.

- ^ "Daughtry to headline WVU FallFest 2008". West Virginia University. Retrieved August 12, 2010.

- ^ a b "WVU hosts annual back to school bash at the Mountainlair". WBOY. Archived from the original on February 25, 2010. Retrieved August 12, 2010.

- ^ a b "WVU Mountaineer Week". West Virginia University. Retrieved August 12, 2010.

- ^ "WVU's Beard Growing Contest". WBOY. Archived from the original on July 24, 2011. Retrieved August 12, 2010.

- ^ "WVU Lights Historic Woodburn Hall". WBOY. Archived from the original on September 2, 2011. Retrieved August 12, 2010.

- ^ "Mountaineer Parents Club Fall 2009". WVU Mountaineer Parents Club. Archived from the original on June 10, 2010. Retrieved August 12, 2010.

- ^ "WVU homecoming". West Virginia University. Retrieved August 12, 2010.

- ^ "WVU Fraternity Recruitment". West Virginia University. Archived from the original on February 3, 2010. Retrieved August 11, 2010.

- ^ Zeller, Karen (Summer 1998). "Mountainlair Turns 50". West Virginia University Alumni Magazine. 21 (2). West Virginia University. Archived from the original on August 28, 2008. Retrieved November 12, 2008.

- ^ "The Lair". West Virginia University. Retrieved August 12, 2010.

- ^ a b "WVU Recreation Center". West Virginia University. Archived from the original on August 18, 2010. Retrieved August 12, 2010.

- ^ "WVU Mountaineer Adventure Program". West Virginia University. Archived from the original on June 26, 2010. Retrieved August 12, 2010.

- ^ "Mon River Trails Conservatory". Monongalia County. Archived from the original on August 19, 2010. Retrieved August 12, 2010.

- ^ "Coopers Rock State Forest". WV State Parks. Retrieved August 12, 2010.

- ^ "WVU Office of Student Activities". West Virginia University. Archived from the original on November 28, 2014. Retrieved November 27, 2014.

- ^ "- WVUENGAGE". wvuengage.wvu.edu.

- ^ "West Virginia Fraternity Pledge Who Died Had a 0.49 Blood Alcohol Level". January 27, 2015.

- ^ "Suit Over Student Death at West Virginia University Frat House Settles for $250K". Insurancejournal.com. December 6, 2018. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ ""Breathe, Nolan, Breathe" documentary brings awareness to dangers of hazing". November 13, 2019.

- ^ "Nolan Burch's family marks the anniversary of death with the documentary "Breathe, Nolan, Breathe"". November 9, 2019.

- ^ ""Breathe, Nolan, Breathe Documentary"". November 14, 2019.

- ^ "WVU Fraternities Break Away After Greek Life Reform". January 30, 2019.

- ^ "West Virginia students disciplined after frat house fall". WHSV. January 22, 2019. Retrieved August 15, 2022.

- ^ "WVU Fraternities Break Away After Greek Life Reform". Campus Safety Magazine. January 30, 2019.

- ^ "Daily Athenaeum 2007–2008 Rate Card" (PDF). West Virginia University DA. Archived from the original (PDF) on May 15, 2008. Retrieved August 11, 2010.

- ^ "Princeton Review Homepage". Princeton. Retrieved August 11, 2010.

- ^ "College Music Journal Press Release". College Music Journal. Archived from the original on October 11, 2007. Retrieved September 30, 2007.

- ^ "Here Are the 2015 College Radio Award Winners". Archived from the original on December 8, 2015. Retrieved December 7, 2015.

- ^ "WellWVU, Student Center for Health". West Virginia University. Archived from the original on August 4, 2010. Retrieved August 13, 2010.

- ^ "West Virginia University Hospitals". West Virginia University. Archived from the original on July 10, 2009. Retrieved August 13, 2010.

- ^ "Rates, Dates & Deadlines for 2014–2015". West Virginia University. Retrieved November 27, 2014.

- ^ "Student Health". WVUH. Retrieved November 27, 2014.

- ^ "Explore West Virginia University".

- ^ "Moller to Build Organ for Creative Arts Center" (PDF). The Diapason. 58 (5): 1. April 1967.

- ^ "West Virginia Public Theater". West Virginia Public Theater. Archived from the original on May 11, 2008. Retrieved August 13, 2010.

- ^ "Home – Art Museum – West Virginia University". Retrieved October 17, 2014.

- ^ "College Football Schedules, Scores, News, Predictions, and Rankings". AthlonSports.com.

- ^ "West Virginia vs. Villanova". ESPN. Retrieved May 23, 2018.

- ^ "Ginny Thrasher - Rifle".

- ^ Vaccaro, Mike (April 3, 2010). "For WVU fans, it's all about Mountaineers". NY Post. Retrieved August 2, 2010.

- ^ Mike, Vaccaro (April 3, 2010). "For WVU fans, it's all about Mountaineers". New York Post. Retrieved October 3, 2010.

- ^ a b "GQ Names the Top Ten Worst College Sports Fans". Archived from the original on May 3, 2012.

- ^ "Rowdy West Virginia student section under fire". Archived from the original on March 10, 2010. Retrieved March 14, 2010.

- ^ "Gainesville Sun - Google News Archive Search". news.google.com.

- ^ "Yahoo". backporch.fanhouse.com.

- ^ a b "Living Here: WVU Traditions". West Virginia University. Archived from the original on July 20, 2011. Retrieved August 6, 2010.

- ^ Forinash, Danny (August 4, 2005). "A Mark to Remember: Flying WV". WTRF-TV. Archived from the original on February 14, 2009. Retrieved November 21, 2008.

- ^ "Branding and Communications at WVU". West Virginia University. Archived from the original on July 20, 2011. Retrieved August 6, 2010.

- ^ "Eyewitness News". Archived from the original on March 8, 2014. Retrieved March 7, 2014.

- ^ "SI: 102 More Things You Gotta Do Before You Graduate". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved August 11, 2010.

- ^ Forward, Jordan (October 8, 2018). "Fallout 76 locations - all the map markers confirmed across post-apocalyptic West Virginia". PC GamesN. Retrieved August 9, 2024.

External links

[edit]![]() Media related to West Virginia University at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to West Virginia University at Wikimedia Commons

- Official website

- West Virginia Athletics website

- . Collier's New Encyclopedia. 1921.

- . . 1914.

- . New International Encyclopedia. 1905.

- West Virginia University

- Universities and colleges established in 1867

- 1867 establishments in West Virginia

- Land-grant universities and colleges

- Education in Monongalia County, West Virginia

- Public universities and colleges in West Virginia

- Flagship universities in the United States

- Tourist attractions in Monongalia County, West Virginia

- Universities and colleges accredited by the Higher Learning Commission